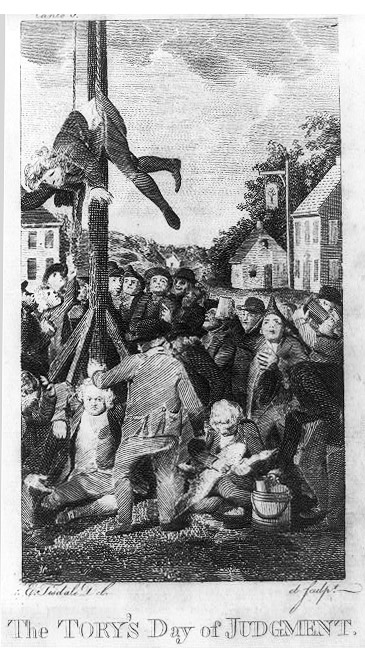

Engraving: A New Hampshire protest against the Stamp Act in 1765

Haverhill

Sir Richard Saltonstall arrived in Salem aboard the Arabella with the Winthrop fleet on June 12, 1630. His son Richard was born in 1610, became a miller and a prominent citizen of Ipswich, but returned to England, where he died in 1694. His son Nathaniel settled at Haverhill, where he is considered to be a founding father.

Richard Saltonstall, the sixth generation from Sir Richard, was born in 1732 and became a colonel during the French and Indian War. He escaped the slaughter of British and American soldiers at Fort William Henry and remained in active service until the close of the war. He was appointed Sheriff of Essex County and resided at the family estate in Haverhill.

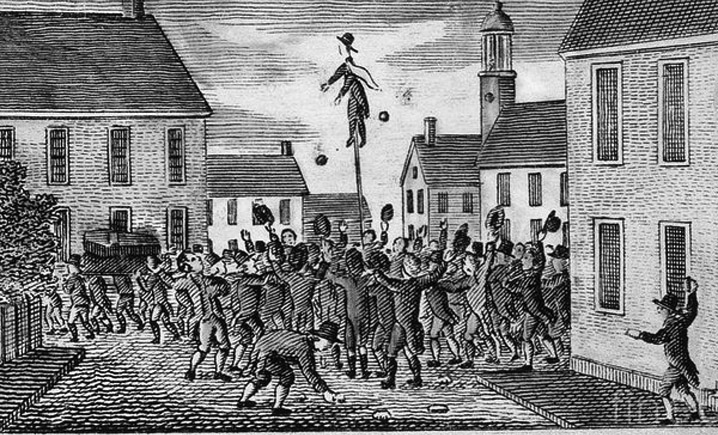

A steady Loyalist, Saltonstall defended the right of the Crown to tax the Colonies. In 1765, a mob from Haverhill and neighboring Salem, NH, proclaiming themselves to be “Sons of Liberty,” marched to his home, armed with clubs. Saltonstall opened his door and told them he was under the oath of allegiance to the King and therefore was bound to discharge the duties of the office he held under him, but that he was as great a friend to the country as any of them. He then ordered refreshments for the assembled crowd, who soon began to relent, and requested them to go to the nearby tavern at his expense, upon which the rioters began to sing his praises.

In October of that year, Saltonstall was removed as regimental commander, and a second mob appeared at his house, led by Timothy Eaton, a member of Haverhill’s Committee of Correspondence, proclaiming that his “bold and unpatriotic words were obnoxious to the public opinion of the town.” Saltonstall promised “to give them no more cause for offense” and was forced to sign a loyalty oath.

In March, 1775 Captain James Brickett of Haverhill raised a company of men “in the cause of liberty” who voted at a meeting that they adopt a uniform consisting of a blue coat with yellow plain buttons, buff or nankeen waistcoat & breeches, and white stockings with half boots or gaiters, and that the hats be cocked alike, and that they should all received a bright gun and bayonet.

Fearing for his safety, Saltonstall fled to Boston, still under control of the British, and was appointed as Captain in the Loyal American Association, assembled to “prevent all disorders within the district by either Signals, Fires, Thieves, Robbers, house Breakers or Rioters.” He left America forever when the British evacuated Boston in March 1776 and settled in London. Refusing to enter the British service against the Colonists, he stated that although he could not conscientiously engage on the side of his native country, he would never take up arms against her.

The treatment of Loyalists is documented in Thomas Gage’s book, The history of Rowley, anciently including Bradford, Boxford, and Georgetown, from the year 1639 to the present time:

Recantations in Rowley

“From the commencement of the troubles with the Mother Country up to 1774, there were those in Rowley who favored the royalists, not because they were actually enemies to the best interests of the Colonies, but because it would, in the end, in their opinion, prove worse than in vain for the Colonies at that time to contend with Great Britain. All such declined to sign the Whig Covenant, and were denominated Tories, enemies to their country, etc. It is believed, however, that, during this year, nearly all such persons, in Rowley, made and signed their recantations, which were published in the prints of the day, and their persons restored to favor. Their recantations were variously expressed, one or two of which follow, viz:

‘Whereas there have been several acts passed of late, by the British Parliament, contrary to our natural and charter rights, which have occasioned some measures to be entered into by the people in general in the American Colonies, in order to defeat such pernicious bills, which are so dangerous in their consequences, from taking place; among which was a Covenant from the Committee of Correspondence in Boston to the towns in this Province, tending to a general non-importation from, and exportation to the island of Great Britain; and said Covenant has been offered to us to sign, and we have refused it.

‘Therefore, we now take this method to inform the public that we are heartily sorry for our so refusing, and do now solemnly promise that we will sign said Covenant at the first opportunity we have. We further solemnly promise to agree to and be assisting in carrying into execution, as far as in us lies, any measures that shall be thought most proper, and be entered into by the people in general, or by the result of the General Congress of these United Provinces. And we do further humbly ask the pardon, and beg forgiveness for our so offending, of the honorable gentlemen now present, and of all the people who are friends of American liberty, as we are deeply sensible we have behaved directly contrary to the welfare and prosperity of the insulted Provinces of North America.—Rowley, October 7, 1774’

“These recantations or submissions were usually made and signed in the presence of a voluntary meeting of the citizens, called for the purpose. At these meetings, it was their practice in Rowley to proceed to organize themselves by the choice of a clerk and a committee, who were to draw up articles that had been alleged against the individual or individuals then before them for examination and trial. The articles being drawn up and read to the meeting, witnesses were then examined, and a vote taken, to see if the evidence was sufficient to support the charges. It was usually decided in the affirmative, as the accused found it difficult to prove the negative side of the question. The committee then prepared a paper, containing the terms of submission and confessions of political transgressions, which the accused were required to sign, by a force too powerful to admit of a refusal.”

“As the War continued, Tory sentiments were met with severe measures. Jonathan Stickney Jr. of Rowley was so unwise that he used very uncomplimentary language regarding the patriot cause and its leaders. He was arrested and sent to the General Court. Its decision was quick and sharp:

“To the Keeper of Ipswich Jail: You are ordered to receive into your custody Jonathan Stickney Jr., who has been apprehended by the Committee of Inspection, Correspondence and Safety of the Town of Rowley and sent to the General Court for having in the most open and daring manner endeavored according to the utmost of his abilities to encourage & introduce Discontent, Sedition, and a Spirit of Disobedience to all lawful authority among the people by frequently clamoring in the most impudent insulting and abusive Language against the American Congress, the General Court of this Colony and others who have been exerting themselves to save the Country from Misery & Ruin all which is made fully to appear.

“You are therefore to keep him safely in close confinement (in a Room by himself & that he be not allowed the use of pens, ink nor paper, and not suffer him to converse with any person whatever unless in your hearing) till the further order of the General Court or he be otherwise discharged bv due course of Law.—In the Name and by the order of the Council and House of Representatives John Lowell, Dep. Sec. Council Chambers April 18, 1776.”

The Committee of Safety of Rowley petitioned the Court on June 5th, 1776, that, in view of his penitence, he be removed from jail to his father’s house, under such restrictions as may be imposed.

In 1778, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts banished hundreds of Loyalists from returning, and his Haverhill home passed into the hands of his brother, Dr. Nathaniel Saltonstall, who had sided with the Patriots.

John Calef of Ipswich

Dr. John Calef was born in Ipswich in 1725, the son of Robert Calef and Margaret, daughter of Deacon John Staniford, and was married to Dorothy Jewett, the daughter of Rev. Jedediah Jewett of Rowley. Dr. Calef served the colony as a surgeon during the “Old French War” but had loyalist leanings and opposed the growing hostility against the British Government.

Dr. Calef represented the town of Ipswich in the General Court for several years, but as a Loyalist, he went against the town’s wishes repeatedly in Boston. He was among only 17 out of 109 members of the Massachusetts Assembly who voted to retract the “Massachusetts Circular Letter,” which was adopted in response to the 1767 Townshend Acts. Calef was replaced as Representative by General Michael Farley, but Ipswich citizens’ anger at Calef lingered as war with England approached.

In the fall of 1774, now six years after Dr. John Calef was removed from office, a great crowd of Ipswich citizens gathered about his residence near the South Green and demanded a formal confession of his wrongful votes. In some towns, Loyalists were chased out of town, but Calef got off relatively easy by making a profuse apology.

The Essex Gazette recorded Dr. Calef’s written statement to the hostile assembly:

“Inasmuch as a great Number of Persons are about the House of the Subscriber, who say that they have heard I am an Enemy to my Country, etc. and have sent a large Committee to me to examine me respecting my principles, in compliance with their request I declare, First I hope and believe I fear God, honor the King, and love my Country. Secondly, I believe the Constitution of civil Government held forth in the Charter of Massachusetts Bay Province to be the best in the whole world, and that the Rights and Privileges thereof ought to be highly esteemed, greatly valued and seriously contended for, and that the late Acts of Parliament made against this province are unconstitutional and unjust and that I will use all lawful means to get the same recovered; and that I never have and never will act by an omission under the new Constitution of Government, and if I have ever said or done anything to enforce said Act I am heartily sorry for it; and as I gave my vote in the General Assembly on the 30th of June 1768, contrary to the minds of the people, I beg their forgiveness and that the good people of the Province would restore me to their esteem and friendship again.”

Sources and Further Reading:

- Untapped History: “I Have No Remorse of Conscience for My Past Conduct” – Haverhill Loyalist Richard Saltonstall”

- Loyalists of Massachusetts and the Other Side of the American Revolution by James H. Stark

- Letters of a Loyalist Lady, by Hulton, Ann, -1779

- The Plight of American Loyalists (American Heritage Magazine)

Related posts:

Ipswich and the American Revolution, Part 2: The Revolutionary War - On June 10th, 1776, the men of Ipswich, in Town-meeting assembled, instructed their Representatives, that if the Continental Congress should for the safety of the said Colonies Declare them Independent of the Kingdom of Great Britain, they will solemnly engage with their lives and Fortunes to support them in the Measure.… Continue reading Ipswich and the American Revolution, Part 2: The Revolutionary War

Ipswich and the American Revolution, Part 2: The Revolutionary War - On June 10th, 1776, the men of Ipswich, in Town-meeting assembled, instructed their Representatives, that if the Continental Congress should for the safety of the said Colonies Declare them Independent of the Kingdom of Great Britain, they will solemnly engage with their lives and Fortunes to support them in the Measure.… Continue reading Ipswich and the American Revolution, Part 2: The Revolutionary War

[…] The Conscience of a Loyalist by Gordon Harris on Historic Ipswich […]

I suspect one of my great grandparents ran to Nova Scotia during the war. Interesting info!

thanks for your breath of truth. all my mother’s family were here during the war… on both sides.. as history is written by the victors, most folk have no clue what really transpired – the story is very complex and well worth the digging one has to do to find the true tale.