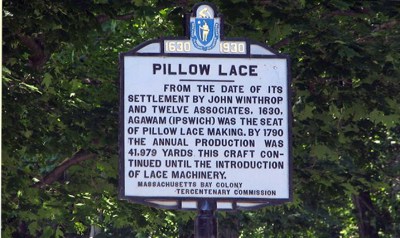

The Pillow Lace plaque is in front of 5 High Street in Ipswich. In the mid-18th Century, a group of Ipswich women started making and selling lace with distinctive patterns. Small round lap pillows were used to pace the bobbins and needles as the lace grew around them. Ipswich lace quickly became very popular and played an essential role during the American Revolution. When George Washington visited Ipswich in 1789, he purchased some black silk lace for his wife, Martha.

Bonnie Hurd Smith explains that “The women were doing it while the men were at war, and many men were killed, so their widows needed to make money to support their families.” Ipswich women used lacemaking as a way to endure. We read in “The Laces of Ipswich” that a yard of lace was “approximately equal in value to a cord of wood or 16 pounds of sheep’s wool.”

In its lace-making heyday in the late eighteenth century, Ipswich, Massachusetts boasted 600 lace makers in a town of only 601 households. At the height of its popularity, the women and girls of Ipswich were producing more than 40,000 yards of lace annually. In the 1820s Ipswich industrialists imported machines from England to mechanize and speed up the operation and opened a factory on this site. Their efforts destroyed the industry. Lace was now mass-produced and no longer a symbol of wealth.

Read more about the pillow lace industry in Fine Thread, Lace and Hosiery by Jesse Fewkes.

The Pillow Lace Site has much history attached to it. One of the early owners of the lot was Dr. Thomas Berry. He was an active supporter of education and served the colony in many ways. But he was a strong-minded character, and drove around town in a chariot with liveried slaves, frequently dressed in red satin breeches and a cape. Citizens would bow respectfully as he passed.

At that time, a path cut across the hill behind his house, leading to a spring at the top of the hill. He obtained permission for the exclusive use of the spring for his family. He would run up the hill with his children every morning for a cold bath. This regimen failed to save them from the terrible throat distemper epidemic, diphtheria, that swept through eastern Massachusetts between 1727 and 1737. Three of his children died.

Dr. John Manning purchased the property and had a home hear for several years. Later, the property became the property of the New England Lace Manufacturing Company, another of the Heard family enterprises. They were attempting to use the new knitting machines to make lace. The thread broke frequently, so they decided to try silk. Augustine Heard brought silkworm cocoons into the country, secured in the waistbands of Chinese coolies to maintain the needed warmth. Mulberry bushes were planted up the hill to provide food, but the silk threads they produced wouldn’t work either. The enterprise was ended, and the building was later passed into the Ross family, who converted it to a Federal-style mansion, torn down circa 1930.

Sources and further reading:

- The Caldwell women: Waldo-Caldwell house

- Fine Thread, Lace, and Hosiery

- Alexander Hamilton and Ipswich Lace

- Ipswich Hosiery

In The Laces of Ipswich: The Art and Economics of an Early American Industry, 1750-1840

, Marta Cotterell Raffel places the Ipswich industry squarely within the wider context of eighteenth-century manufacture, economics, and culture. Identifying what differentiates Ipswich lace from other American or European lace, she explores how lace makers learned their skills, and how they combined a traditional lace-making education with attention to market-driven changes in style. Showing how the shawls, bonnets, and capes created by the lace makers often designated the social position or political affiliation of the wearer, she offers a unique and fascinating guide to our material past.

Ipswich Hosiery - After the first stocking machine was smuggled from England to Ipswich in 1822, immigrants arrived in Ipswich to work in the cotton and hosiery mills, contributing to the town's diverse cultural heritage.… Continue reading Ipswich Hosiery

Ipswich Hosiery - After the first stocking machine was smuggled from England to Ipswich in 1822, immigrants arrived in Ipswich to work in the cotton and hosiery mills, contributing to the town's diverse cultural heritage.… Continue reading Ipswich Hosiery  Ipswich Pillow Lace - In the late eighteenth century, Ipswich had 600 women and girls producing more than 40,000 yards of lace annually. Ipswich industrialists imported machines from England to mechanize and speed up the operation, which destroyed the hand-made lace industry. … Continue reading Ipswich Pillow Lace

Ipswich Pillow Lace - In the late eighteenth century, Ipswich had 600 women and girls producing more than 40,000 yards of lace annually. Ipswich industrialists imported machines from England to mechanize and speed up the operation, which destroyed the hand-made lace industry. … Continue reading Ipswich Pillow Lace  President Washington Visits Ipswich, October 30, 1789 - On October 30, 1789, Washington passed through Ipswich on his ten-day tour of Massachusetts. Adoring crowds greeted the President at Swasey’s Tavern (still standing at the corner of Popular and County Streets) where he stopped for food and drink.… Continue reading President Washington Visits Ipswich, October 30, 1789

President Washington Visits Ipswich, October 30, 1789 - On October 30, 1789, Washington passed through Ipswich on his ten-day tour of Massachusetts. Adoring crowds greeted the President at Swasey’s Tavern (still standing at the corner of Popular and County Streets) where he stopped for food and drink.… Continue reading President Washington Visits Ipswich, October 30, 1789

Thanks Gordon Harris for the post of the Ipswich Pillow Lace, amazing historical description as you always give. Do you have information of Captain Richard Sutton? His mother was Elizabeth Foster Sutton and his sister Mary Sutton, you mentioned both in this post. Captain Richard Sutton was born 20 April of 1870 in Ipswich, Massachusetts, USA and died 23 August 1857 in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Kind regards.

Capt. Richard Sutton was the son of Richard and Elizabeth Foster Sutton, who married in 1758. He was born in 1780 (not 1870). His father’s profession was “leather breeches maker.” During the Revolutionary War, Richard Sr. was a 1st Lieutenant in Col. Timothy Pickering’s regiment, which marched to Providence and Dansbury CT. He or his father was one of the signers in the establishment of the Baptist Church in Ipswich in 1806. Richard Sr. purchased the historic Matthew Perkins House on July 26, 1768, and this is where Captain Richard Sutton was born in 1780. For many years it was known as “The Sutton House.” https://historicipswich.net/8-east-st-matthew-perkins-house/. Captain Richard Sutton married Lucy Lord in 1802. His ships included an older ship called “The Boxer,” and “The General Kleber.” He sailed a steamboat the Potomac to Buenos Aires in 1835. In 1845 while in Buenos Aires he became paralyzed on one side. He died Buenos Aires in 1857, and his wife Lucy died of yellow fever in Buenos Aires in 1871.

Thank you very much Gordon Harris for your answer. I am from Buenos Aires, Argentina. It is very interesting your history posts about Ipswich, I enjoy a lot reading and sharing it with my family. We descends from Captain Richard Sutton. Do you have information about Captain Richard Sutton´s father in-law, Dr. Josiah Lord, he got an illness in Valley Forge during the American Revolutionary War?

Love this lace history! It is also interesting to note that the lace pillows were stuffed with Ipswich Marsh salt grass, which explains how these pillows lasted so long, the salt hay being a deterrent to rodents. Ipswich lacemaking is still alive, taught by Karen Thompson, who replicated the pillows and carved bobbins from bamboo for the Museum. Her book is entitled The Lace Samples From Ipswich. Massachusetts, 1789-1790. I believe it has patterns for all the surviving samples of Ipswich bobbin lace.

Gordon: Excellent historical information, as is the norm with you. Thanks. Bob