Original documents in the Town Clerk’s office show that in April 1657, the Town Meeting appropriated £6 to build the family of Alexander Knight a small thatched roof house on High Street, 16 feet long, 12 feet wide, and 7 or 8 feet high.

In 2013, a group of volunteers began reconstructing the Alexander Knight House next to the Whipple House at the South Green and gifted it to the Ipswich Museum.

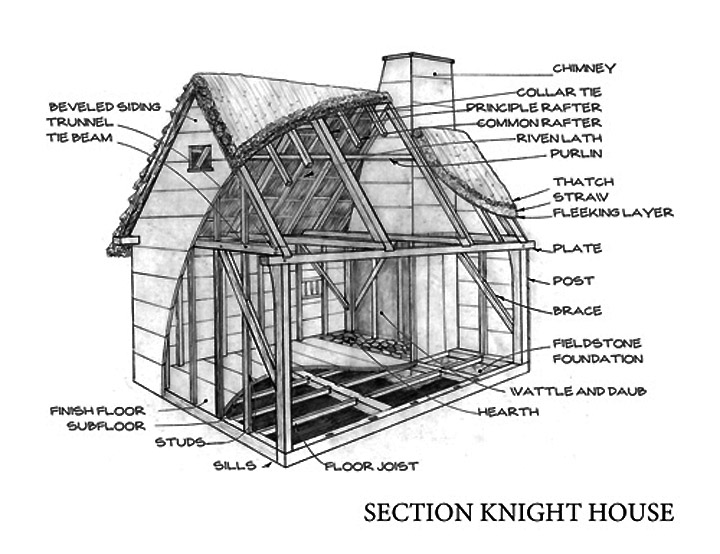

The small English-style timber frame house from 1657 was built with traditional tools, materials, and construction methods of the First Period, complete with a stone foundation, timber frame, wattle and daub chimney, water-sawn white oak boards, and thatched roof. Jowled posts, girts, and braces were fitted to form an end wall, after which plates, studs, joists, principal rafters, and purlins were pegged in place to complete the frame.

Alexander Knight was from Chelmsford, Essex, England, and his wife Anna (or Hannah) Tutty was from London. They arrived in Ipswich in 1635 with sufficient resources, were granted land as was customary in the early years of settlement, and built a home on High St. just beyond the cemetery. Their lives took several bad turns, including the death of their child Nathaniel in 1648 when his clothes caught on fire.

A jury was impaneled concerning the death: six from Ipswich, three from Newbury, four from Rowley, and one from Andover. Knight was fined for carelessness in not preventing a fire after being warned.

Aprill 27th, Anno: 1648: “Whereas it was appoynted by the Court y‘ a jury Should be panelled, to make dew enquiry concerninge the death of Nathaniel Knight, the child of Alexander Knight, we whoe have Subscribed our names, do find it thus, that the child was left aloane in the house, the parents being both gone out, & in that interim of theire absence had its clothes fired, & so was burnt from head to foote, the which was the cause of its death. —Marke Simonds. Thomas Brewer. Francis Dane, Richard Kimball. Henry Kingsbury, John Denyson, Thomas Smith. Haniell Bosworth, Moses Pengry, Thomas Hart, Allan Perly.” (Ipswich Deeds 1:53)

Knight faced the court several other times for charges that included lying and threatening Richard Shatswell:

The family lost their house in the same fire and began boarding with Aaron Pengry under an arrangement with the town. By 1656, Alexander Knight was indigent, had sold his land, was working as an indentured servant, and Pengry asked the town to end the arrangement. A long discussion arose at the April 1657 Town Meeting about how to help the family. The town took mercy and voted to provide him a piece of land “whereas Alexander Knight is altogether destitute, his wife also neare her tyme.” The vote provided that it should be 16 feet long, 12 feet wide, 7 or 8 feet stud, with thatched roof, for which £6 was appropriated. The new house upon which this house is modeled was located on High Street near Lord’s Square.

Alexander Knight

Alexander Knight, who kept an inn at Chelmsford, England, is believed to have come to New England in 1635. His wife was Hannah or Anne, daughter of William Tutty, gentleman, living in England., Her father referred to her as “lately married ” in 1640. Knight owned land in Ipswich in 1636 and was listed as a commoner there in 1641. On Apr. 27, 1648, an inquest was conducted about the death of his son Nathaniel, who had burned to death while having been left alone in the house.

“Alexander Knight’s will, dated Feb. 10, 1663, proved March 29, 1664, was witnessed by John Whipple, James Chute, who wrote it, and Robert Lord. He devised house, house-lot, and planting land to his wife Hannah for life, appointed her and William English of Boston to be executors, and mentioned son Nathaniel born Oct. 16, 1657, and daughters Hannah, Sarah, and Mary. His house with thirty-two acres of land was appraised at one hundred thirty-seven pounds eighteen shillings and eleven pence.

“Alexander Knight’s wife, Hannah Tutty, was a daughter of William Tutty of St. Stephen’s, Coleman Street. London, gentleman. When William Tutty died in January 1640, his will stated, “Item, because I have already given unto my eldest daughter Anne, lately married with Alexander Knight of Ipswich in New England beyond the seas, a competent marriage portion, I therefore give unto her, in full of her child’s portion, the sum of ten pounds more to be paid her also by mine executrix within one year next after my decease.”

William Tutty’s son John Tutty, a fruiterer of London died 3 September 1657, and his will was proved a month later, which stated, “To my sister Hannah Knight of New England for her children, or such of them living, or in case they be all deceased then for her own use if living at the time, I shall herein appoint for the payment of this and other legacies fifty pounds.”(5)

Subsequent History of the Alexander Knight House

After their mother’s death, the property was apparently divided between the three surviving siblings (including daughters Hannah and Mary). Their daughter Hannah Knight, born in Ipswich about 1650, married Isaac Perkins there. about 1669, since their first child was born July 1, 1670.” 3

The location of Alexander Knight’s house was on High Street, confirmed by a 1655 deed by Allan Perlye to Walter Roper, having the house & land of Alexander Knight toward the northwest, and the land of Richard Kimball sen’r. toward the northeast. (Ipswich deeds 2:44)

On March 19, 1718, Isaac Perkins of Chebacco and his wife, Hannah Knight, for a sum of five pounds, sold to Richard Kimball of Ipswich, a joiner, one full third of the rights in the common “that did belong to her father, Alexander Knight,” including woodland, upland, and thatch ban (Book 36: Page 122).

Mary Knight, the daughter of Alexander and Hannah Knight married first, John Gamage, and Gamage sold 1/3 of the house lot to Richard Kimball in 1715, but Kimball Jr. sold it back to Gamage in 1721. (4)

After Gamage’s death, Mary married Henry Osborn. On April 12, 1721, Mary Osborn, widow of Henry Osborn late of Ipswich, sold to Richard Kimball of Ipswich, joiner, in consideration of three pounds thirteen shillings, 1/3 of a wood lot and thatch lot that belonged to her father, Alexander Knight. (Book 39: Page 110)

Sources:

- Records of the Essex Courts

- Historical Collections of the Essex Institute, Volume 33: Waters, Thomas. “The Early Homes of the Puritans”

- Paul, Edward Joy. The Ancestry of Katharine Choate Paul: now Mrs. William J. Young Jr. (Milwaukee, WI: Burdick & Allen, 1914) p 129.

- Waters, Thomas. Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Vol 1

- Waters, Henry Fitz-Gilbert, A.M.. Genealogical Gleanings in England.

Construction of the Alexander Knight house

by John Fiske:

The Alexander Knight House that now stands on the South Green is an exact replica of a seventeenth-century, single-room house – the sort that many of the humbler first settlers would have lived in. Normally, Historic Ipswich does not write about reproduction houses. But what should we do if there is no original? None of these early single-room houses have survived. As we all know, history is written by the winners, and the winners didn’t live in houses like this. The larger houses that were owned by the prosperous families, such as the Whipple House or the Heard House, tell the dominant history of Ipswich, but the humble history often disappears – the humble houses and their humble furnishings were not thought worth saving, so they weren’t. An accurate replica is often the only way to bring “humble history” to life. Ipswich is unique in having so many of these (larger) first-period houses; it is also unique in having among its town records the only written description of a single-room house, and now it is unique in having the house itself.

Alexander Knight

Alexander Knight was an early settler of Ipswich, and was a man of some substance, both here and in England before he emigrated in 1634. He appears regularly in the town records, but the first hint of trouble comes in March, 1654, when he was fined 20 shillings for “carelessness in not preventing a fire after warning.” It appears that his young son died in the fire. This fire appears to have caused his downfall and may have injured him so badly that he was unable to work. At any rate, in 1656 he leased out his land and cattle, which suggests he was no longer capable of farming, and in April of that year the town records tell us “Alexander Knight being in the house of Aron Pengry for the present necessity, the selectmen think it meet that he should free his house agayne by the first of May next.”

The way the town cared for its poor and homeless was to house them with other residents, often as indentured servants. Alexander Knight may have been a bit ornery as a lodger and may not have been able to work, for it sounds as though Pengry had petitioned the selectmen to eject him. Certainly Knight does not come across too well in the record for March, 1657:

“Whereas Alexander Knight hath often complayned to us of his want of an habitation & that he is altogether destitute his wife alsoe being neare her tyme, and that not withstanding all his endeavor he hath not been able to provyd reliefe in this Dir___ & therefore is forced to complayne to the Town for helpe. The selectmen conssidderinge there is noe common house provided in such cases & being informed that Mr. John Cogswell hath an empty house at his disposing wherewith the sayd Alexander may be Comfortably relieved in his nesesity it is therefore ordered that the constable shall repair to the sd Mr. Cogswell (and if he shall engage) shall require him to give him entrance into the sayd house for the present reliefe of ye sd Alexander…”

For some reason, Knight never ended up in Cogswell’s house (did Cogswell know his reputation, we wonder?), for in April 1657, we come across the record that really interests us: it is the only extant description of a seventeenth-century single-room house.

“It is ordered that Mr. Willson shall desire and is hereby empowered to secure a house to be built for Alexander Knight of 16 foot long & twelve foote wyde & 7 or 8 foote stud upon his ground & to pryd [provide] thatching & other things nesasary for it & in case he cannot secure carpenters otherwise to secure carpenters to work a day apiece & other workingmen upon the penalty of five shillings a day if they refuse.”

(The selectmen regularly required men to give a day’s labor to public works such as maintaining the roads or building bridges.)

So that is the house the town built for Alexander Knight in 1657. And that is the house that has been replicated by volunteers and completed in 2015.

The pictures below tell the story of the construction of the house.

Construction

All the wood for the original house was sawn in the sawmill on the Lower Falls of the Ipswich River. The wood for the replica was sawn in a virtually identical mill at the Taylor Sawmill, in Derry, NH. To saw the dense white oak for the frame and the large pine logs for the siding the mill had to be run at the slowest speed. The saw marks are clearly visible on the floorboards in the photographs of the interior of the house.

The fieldstone cellar provided climate-controlled storage throughout the year: cool in summer and above freezing in winter. The section on the far left, with fieldstones laid on the ground, is the base of the hearth. The cellar walls provided the foundation for the sills, keeping them off the damp ground.

The cellar is reached by a trap door near the hearth. Note the marks of the reciprocating saw on the floorboards.

The Hearth and Chimney

The hearth was completely open, its wooden walls “catted” (coated) with a clay lining that continued up the chimney. This would not have been allowed in Boston: “Wee have ordered that noe man shall build his chimney with wood nor cover his roof with thatch, which was readily assented to, for that divers houses have been burned since our arrival (the fire always beginning in the wooden chimney)…” Thomas Dudley, 1631.

Thatching

In smaller towns like Ipswich, thatching was allowed despite the fire danger. Thatched roofs were cheap, warm, dry and durable – qualities that outweighed the fire risk.

Windows

A window with sliding shutters.

A glazed window has been fitted in the front here for educational/illustrative purposes even though it would probably have been too expensive for the original house. In some houses of the period the unglazed windows were covered with oiled paper, but this is not documented in any Ipswich house.