Excerpts from Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, by Thomas Franklin Waters

In 1767, the Townshend Acts were passed, one of which provided for a tax on wine, glass, tea, gloves, etc, imported into the Province. During the winter, the General Court issued a Circular Letter, which was sent to the other Assemblies, notifying them of the measure adopted by Massachusetts concerning resistance to the Townshend Acts and suggesting concerted action.

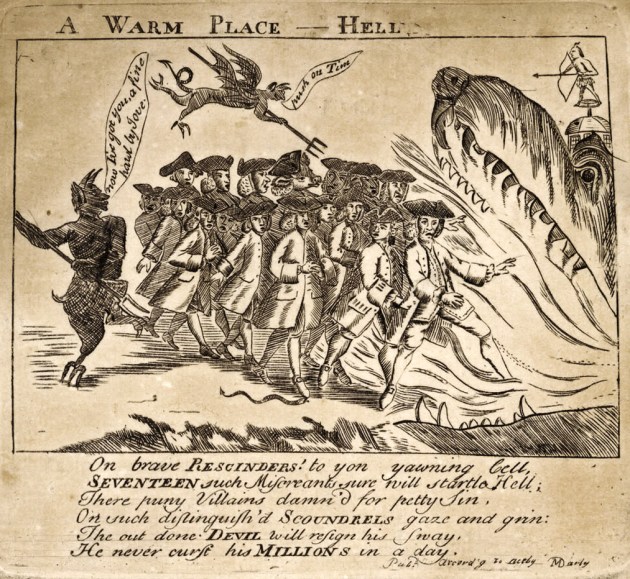

Dr. John Calef was the representative from Ipswich to the General Court in Boston but was among only seven members of the Massachusetts Assembly who voted to retract the Circular Letter. As war with Britain loomed closer and closer, Ipswich citizens’ anger at Calef grew.

Calef was immediately replaced as Representative by General Michael Farley. To deprive the Townshend Acts of all value as a measure for revenue, Boston, Ipswich, and other large towns took spirited measures. At an Ipswich Town meeting, held on March 19, 1770, a committee, previously appointed, reported as follows :

“Taking under consideration the Distrest State of Trade, by Reason of a Late Act of Parliament Imposing Duties on Tea….Voted, that we will abstain there from ourselves & Recommend the Disuse of it in our Families, Until all the Revenue Acts are Repealed.”

Upward of three hundred “Mistresses of Families” in Boston bound themselves to “totally abstain from Tea (sickness excepted) not only in our respective families but that we will absolutely refuse it if it should be offered to us upon any Occasion whatsoever.” A hundred and twenty-six young ladies of Boston signed a similar agreement. The women of the resistance called themselves the “Daughters of Liberty.”

The Ipswich Resolves of 1772

At a Town meeting on Dec. 28, 1772, Ipswich made its response to the Boston Protest in a lengthy and elaborate series of Resolves, which included the following:

- The right of the Colonists to enjoy and dispose of their property in common with all other British subjects.

- The unwarranted assumption of power by Parliament to raise a revenue contrary to the minds of the aggrieved and injured people, the expenditure of this revenue in providing salaries, which rendered the Governor and Judges independent of the people.

- The neglect of their petitions for redress

- A resolution to choose a Committee to correspond with the Committees of other towns.

The Report was read to the assembled Ipswich Town Meeting and put to vote, paragraph by paragraph, and unanimously adopted. Capt Farley, Mr. Daniel Noyes, and Major John Baker were chosen as the Committee of Correspondence, “to Receive and Communicate all salutary measures that shall be proposed or offered by any other Town.”

Tea Protests Erupt

On December 3, 1773 in Charleston, South Carolina. Christopher Gadsden and the Sons of Liberty seized tea from a ship and placed it in the Exchange Building. The December 16, 1773 edition of the Massachusetts Spy reported that on December 12, “the patriotic inhabitants of Lexington unanimously resolved against the use of Bohea tea of all sorts, Dutch or English importation; and to manifest the sincerity of their resolution, they brought together every ounce contained in the town, and committed it to one common bonfire.”

The best-known event was on Dec. 16, 1773, when tea was thrown into the Boston Harbor. Two weeks later in Provincetown, locals seized a grounded ship’s cargo of tea and took it to the Fort at Castle Island, but seven men dressed as Mohawks took the three chests of tea and burned them. Similar protests occurred in Princeton and New York over the following months. On March 6, about sixty men boarded a ship in Boston and dumped another twenty-eight chests of tea into the harbor.

The Ipswich Resolves of 1773

A week after the tea was dumped in Boston on Dec. 16, Ipswich citizens met in the most violent mood, and adopted a series of Resolutions:

- That the Inhabitants of this Town have received real pleasure and Satisfaction from the noble and spirited Exertions of their Brethren of the Town of Boston and other Towns to prevent the landing of the detested Tea lately arrived there from the East India Company subject to a duty for the sole Purpose of Raising a Revenue to Support in Idleness and Extravagance a Set of Miscreants, whose vile emissaries and Understrappers swarm in the Sea Port Towns and by their dissolute Lives and Evil Practices threaten this Land with a Curse more deplorable than Egyptian Darkness.

- That we hold in utter Contempt and Detestation the Persons appointed Consignees …. who have rendered themselves justly Odious to every Person possessed of the least Spark of Ingenuity or Virtue in America.

- That it is the Determination of this Town that no Tea shall be brought into it during the Term aforesaid and if any Person shall have so much Effrontery and Hardiness as to offer any Tea to sale in this Town in Opposition to the general Sentiments of the Inhabitants he shall be deemed an Enemy to the Town and treated as his superlative Meanness and Baseness deserve.”

A tradition of the Farley family is that when the embargo on tea went into effect, Gen. Farley would not allow any tea in his home, but his wife would occasionally visit her neighbor, Dame Heard, and enjoy a cup of tea. She was, however a Patriot, and when a regiment of men were preparing for battle, with her own hands she filled each man’s powder horn with powder which was stored in the garret of her house.

The Ipswich Convention

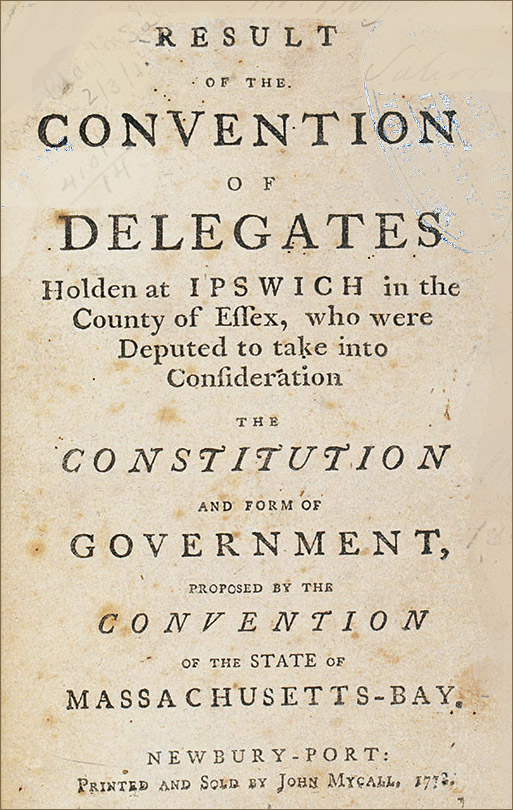

Wild rumors of bloodshed abounded. Delegates from all the towns, 67 in number, arrived in Ipswich on Tuesday, Sept. 6, 1774, and the Ipswich Convention began its deliberations, which required two days. Jeremiah Lee Esq. of Marblehead was the Chairman. Resolutions were adopted by unanimous vote, binding themselves to stand together in opposition to the Crown, demanding the resignation of officials holding office by Royal appointment, and declaring the Provincial Congress, soon to assemble, absolutely necessary for the common safety. The Ipswich Convention was “held by adjournment” on April 29, 1778, to review the proposed Constitution framed by the Convention of the State. This Convention was then adjourned to May 12, to be held at Ipswich.

First Provincial Congress

The First Provincial Congress met in Salem on Friday, October 7, 1774, Ipswich being represented by Capt. Michael Farley and Mr. Daniel Noyes. At the Town Meeting held on November 21, the Proposals and Resolves of the Continental Congress being read, the vote was put to the Town to approve of said Proposals and Resolves. It passed in the Affirmative unanimously.

On Nov. 21, 1774, the crisis was at hand. The enlistment of soldiers according to the Proposals of the Provincial Congress was approved, and a plot of land at the easterly end of the Town House, fifty feet long and twenty-five feet wide was granted to “Erect a House for the Encouragement of Military Discipline.”

On June 10, 1776, Ipswich Town Meeting voted the following:

“The representatives shall be instructed if the Continental Congress should for the safety of the Colonies declare them independent of Great Britain, the inhabitants here will solemnly pledge their lives and fortunes to support them in the measure.”

Soon the war was on. A price was put on the head of John Calef, and he fled with his family to Castine near the Penobscot Peninsula, where he worked as a surgeon for the British troops.

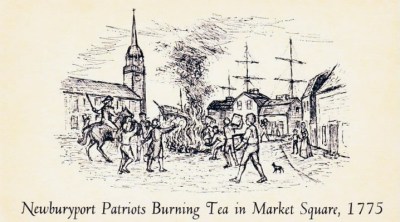

The Newburyport Tea Party - When Parliament laid a tax on tea, the British locked all the tea that had arrived in Newburyport into the powder house. Eleazer Johnson led a group of men who shattered the door and burned the tea in Market Square.… Continue reading The Newburyport Tea Party

The Newburyport Tea Party - When Parliament laid a tax on tea, the British locked all the tea that had arrived in Newburyport into the powder house. Eleazer Johnson led a group of men who shattered the door and burned the tea in Market Square.… Continue reading The Newburyport Tea Party  Madame Shatswell’s Cup of Tea - Madame Shatswell loved her cup of tea, and as a large store had been stored for family use before the hated tax was imposed, she saw no harm in using it as usual. News of the treason spread throughout the town.… Continue reading Madame Shatswell’s Cup of Tea

Madame Shatswell’s Cup of Tea - Madame Shatswell loved her cup of tea, and as a large store had been stored for family use before the hated tax was imposed, she saw no harm in using it as usual. News of the treason spread throughout the town.… Continue reading Madame Shatswell’s Cup of Tea  The “Detested Tea” and the Ipswich Resolves - On Dec. 16, 1773, the tea brought into Boston harbor was thrown into the sea. A week later, Ipswich citizens met in the most violent mood, and adopted a series of resolutions,… Continue reading The “Detested Tea” and the Ipswich Resolves

The “Detested Tea” and the Ipswich Resolves - On Dec. 16, 1773, the tea brought into Boston harbor was thrown into the sea. A week later, Ipswich citizens met in the most violent mood, and adopted a series of resolutions,… Continue reading The “Detested Tea” and the Ipswich Resolves