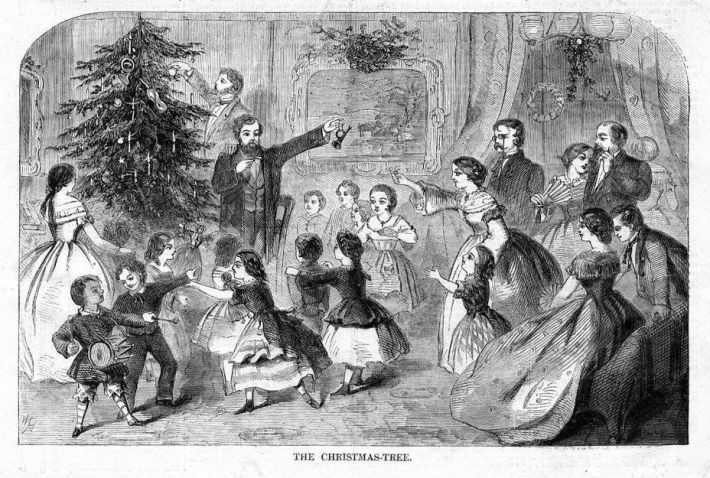

With its “storybook” downtown, Ipswich, Massachusetts would seem like the natural setting for a Colonial-era Christmas, but here in Massachusetts, the Puritans shunned Christmas for its pagan roots. In this raw frontier, they dedicated themselves to their labors and God, allowing only Thanksgiving as a time for feasting.

Plymouth Plantation governor William Bradford stopped a Christmas celebration in 1621:

“On the day called Christmas Day, the Governor called them out to work as was used. But the most part of this new company excused themselves and said that it went against their consciences to work on that day. So the Governor told them that if they made it a matter of conscience, he would spare them till they were better informed; so he led away the rest and left them. But when they came home at noon from their work, they found them in the street at play, openly; some pitching the bar, and some at stoolball and such like sports. So he went to them, took away their implements, and told them that was against his conscience, that they should play and others work. If they made the keeping of it a matter of devotion, let them keep their houses; but there should be no gaming or reveling in the streets. Since then, nothing has been attempted that way, at least openly.”

![BAL_368428CHRISTMAS_sml_0[1]](https://historicipswich.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/e152e-bal_368428christmas_sml_01.jpg)

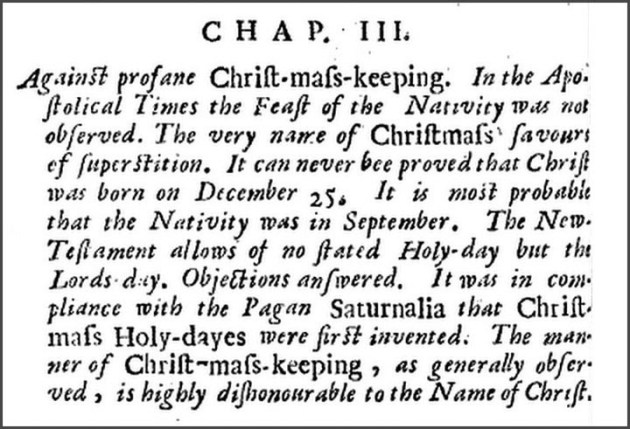

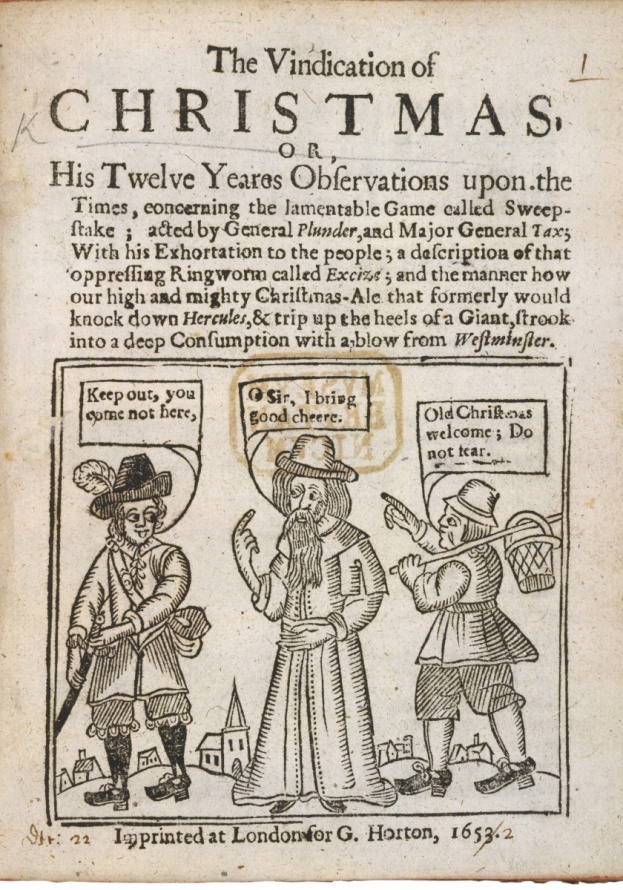

King James ruled England from 1603–1625 and assumed control of the Anglican Church to reinforce the monarchy. In 1617, King James sought to impose various ceremonies designed to enhance the Episcopal cause, including the observance of Christmas and Easter.

In June 1647, with the English Civil War and the ascent of Puritan Oliver Cromwell, the traditional religious festivities were abolished by order of the two Houses of Parliament sitting at Westminster.

“Forasmuch as the feast of the Nativity of Christ, Easter, Whitsuntide, and other festivals, commonly called holy days, have been heretofore superstitiously used and observed; be it ordained, that the said feasts, and all other festivals, commonly called holy days, be no longer observed as festivals; any law, statute, custom, constitution, or canon, to the contrary in anywise notwithstanding.”

The monarchy was restored under King Charles II in 1660, along with the celebration of Christmas.

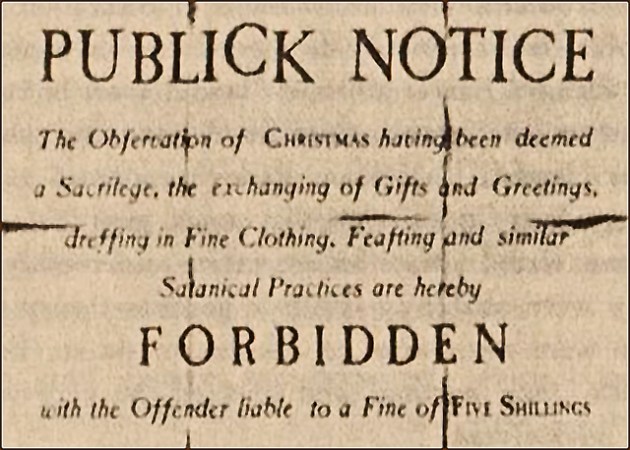

In 1659, a law was passed by the General Court of Massachusetts Bay Colony, imposing a five-shilling fine on any persons found “observing any such day as Christmas or the like, either by forbearing of labor, feasting, or any other way.” The Massachusetts Assembly met in 1667 to revise certain laws annulled by Charles, and once again prohibited the observance of Christmas as a relic of Episcopacy.

Charles II’s successor, King James II, revoked the charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and imposed Sir Edmond Andros as governor, who revoked the Christmas ban in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, giving irate colonists yet another reason not to celebrate the day.

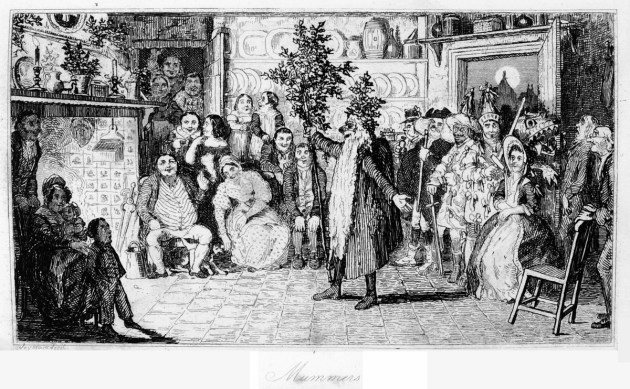

Anticks and Mummers

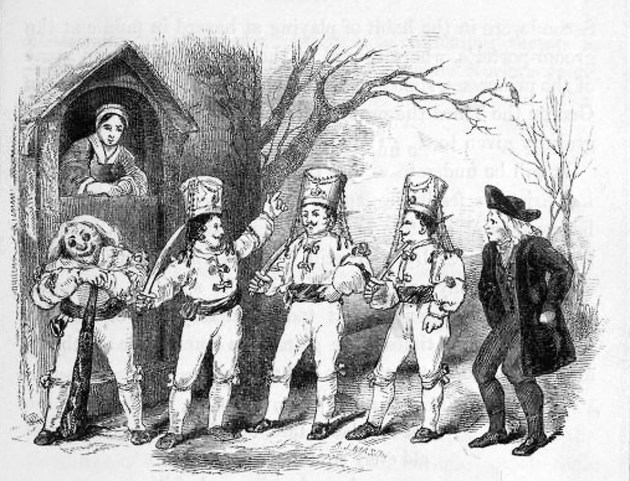

The Puritans turned a blind eye to revelry on Guy Fawkes Day (November 5). The tradition was carried with the English settlers in America, celebrating the failed attempt by Guy Hawkes, a Catholic, to blow up the king and members of Parliament, by parading through towns, performing skits, and stealing from the unfortunate recipients of their spectacles. Esther Forbes wrote in her book, Paul Revere and the World He Lived In, “For twenty-four hours Boston was in the hands of a mob which custom, if not law, had legalized.” The town of Newburyport voted, on October twenty-fourth, 1774, that no effigies be carried about or exhibited on the fifth of November, only in the daytime.

European settlers in many of the American colonies celebrated not only Christmas Day but most of December with revelry. Virginia settlers celebrated the harvest and opened their homes to all Yuletide visitors. In Boston, the upper and middle class would have none of it, but groups of working men derided as “Anticks” would don disguises and go door-to-door demanding money to perform crude skits, all the while drinking the unfortunate hosts’ wassail and beer. In Britain and Ireland, they were called “mummers.” It was trick or treat at Christmas, and it was best to give them some money and suffer through the “performance.”

The 18th Century

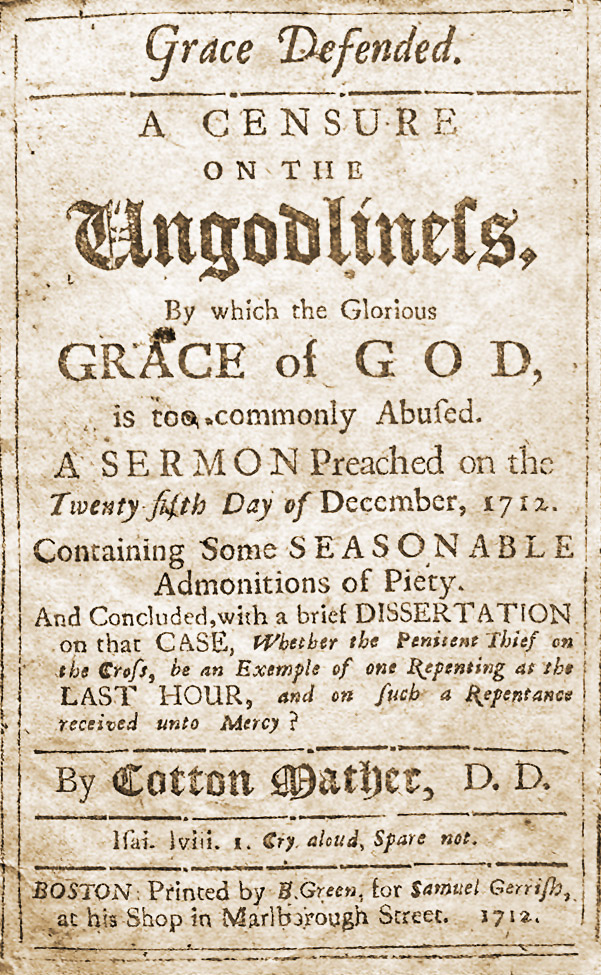

Massachusetts Puritans continued to boycott Christmas into the 18th century. In 1712 Cotton Mather told his Boston congregation that “the feast of Christ’s nativity is spent in reveling, dicing, carding, masking, and in all licentious liberty…by mad mirth, by long eating, by hard-drinking, by lewd gaming, by rude reveling!”

A search of “Christmas” in Thomas Franklin Waters’ book “Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony” indicates Ipswich continued to treat Christmas as any other day into the early 19th Century:

- On Christmas day, 1753, the Court in Ipswich was informed by Mr. Burley’s son, Andrew that his father was dead, and thus repairs to the Ipswich Jail were still incomplete. He was instructed to carry the work forward.

- “On Christmas day, 1753, Jeremiah Lee of Marblehead, “for giving Rings and Gloves more than are allowed by law at the funeral of his father, Samuel Lee was fined £50, half to be given to Edmund Trowbridge, Esq., the informer and the other half to the poor of Marblehead.”

- “On Christmas day, 1817, a committee reported, recommending the purchase of the farm of John Lummus, the erecting of necessary buildings for the accommodation of the Town wards, and an appropriation of not less than $7500. On New Year’s Day, 1818, $10,500 was appropriated for this purpose.”

- Construction of the first Methodist meeting house was begun in September 1824. It was completed in December, and the sale of the pews was held on Christmas Day.

The Unitarians

![illustration_christmas_tree_children[1]](https://historicipswich.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/59959-illustration_christmas_tree_children1-e1668463236670.jpg?w=630)

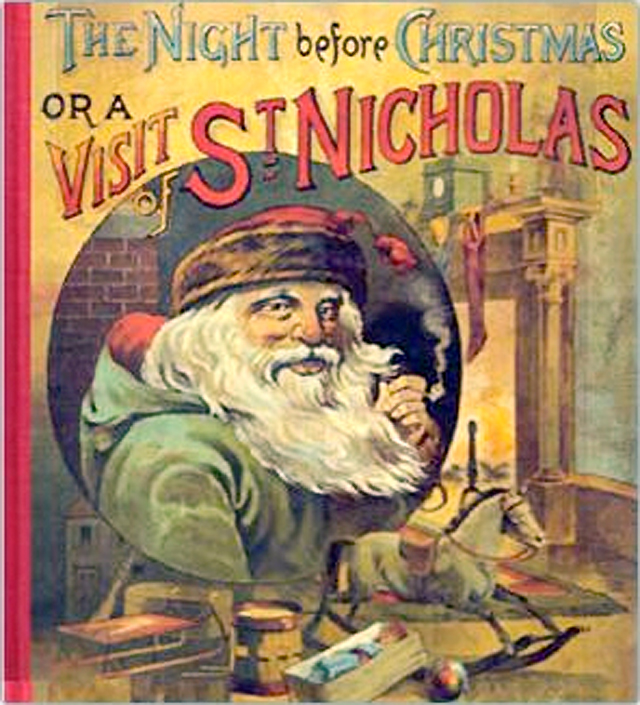

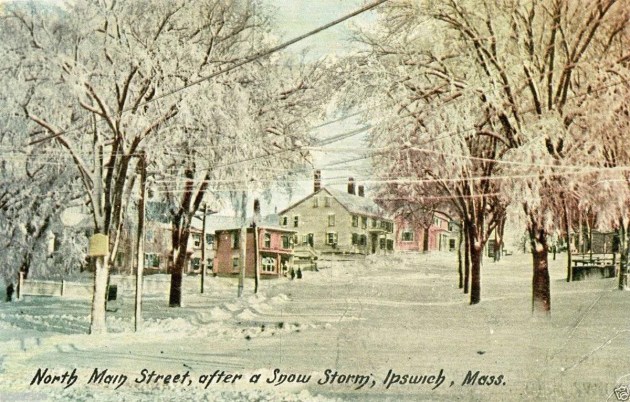

Resentment after the American Revolution prolonged hostility to this “English celebration” for decades. In the late 18th Century, Unitarians reinvented the celebration of Christmas as a tradition to teach children about generosity and unselfishness. The Universalist community in Boston held a Christmas Day service in 1789, and they, along with the Unitarians, became the foremost advocates of religious observance of Christmas.

In “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” written in 1823, Clement Moore a Unitarian, transformed a historic bishop known for his works of charity into today’s Santa Claus. Harriet Martineau, an English Unitarian and journalist who was visiting Boston described the unveiling of what is believed to be the first Christmas tree in New England at the Cambridge home of Unitarian minister Charles Follen in December 1832:

“It really looked beautiful; the room seemed in a blaze, and the ornaments were so well hung on that no accident happened, except that one doll’s petticoat caught fire…The children poured in, but in a moment every voice was hushed. Their faces were upturned to the blaze, all eyes wide open, all lips parted, all steps arrested….I have little doubt that the Christmas tree will become one of the most flourishing exotics of New England. ”

Alabama made Christmas a legal holiday in 1836, followed by Louisiana and Arkansas in 1838, with Massachusetts finally coming around in 1856. In 1870, President Ulysses S. Grant signed into law a bill formally declaring Christmas a Federal holiday.

The old historic neighborhoods in Ipswich look much as they did two or three centuries ago (but much better painted). Tasteful holiday wreaths decorate doors, and candles are in the windows, but in Ipswich, you are less likely to see an inflatable Santa in the front yard.

Further reading:

- Sandys, William (1792-1874): Christmastide, its History, Festivities, and Carols

- Nissenbaum, Steven, The Battle for Christmas

- Reed, Kevin: “Christmas: An Historical Survey Regarding Its Origins and Opposition to It.”

- Crump, William D.” “The Christmas Encyclopedia, 3rd edition“

- The Unitarian and Universalist Invention of Christmas” (Harvard Square Library)

- A Unitarian Christmas

- The Stranger’s Gift

- A Visit from St. Nicholas

![hith-puritan-christmas[1]](https://historicipswich.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/8c941-hith-puritan-christmas1.jpg?w=630)

Very informative. Thank you.

[…] “If anyone had the ‘war on Christmas,’ it was the Puritans,” he said. His talk and slides can be seen here. […]