Towns throughout Massachusetts united in opposition to a series of acts by Parliament to raise funds, including the Sugar Act of 1764, the Stamp Act of 1765, and, in 1767, the Townshend Acts, which taxed wine, glass, gloves & tea, etc. imported into the Colonies.

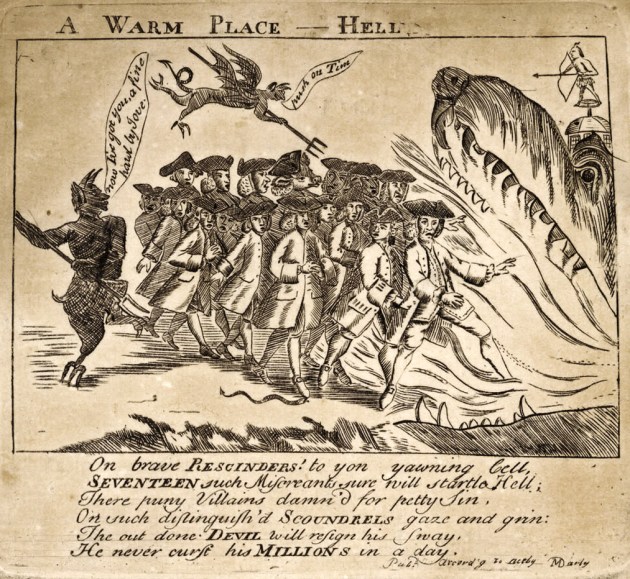

That winter, the General Court issued a Circular Letter suggesting that Great Britain had no right to tax the Thirteen Colonies without their representation in government. Governor Bernard threatened to dissolve the General Court if the letter was not rescinded. Paul Revere issued this broadside condemning the 17 representatives who voted to rescind, including Dr. John Calef of Ipswich, who was promptly booted out of the job. Michael Farley became our representative.

By early 1770, more than 2,000 British soldiers occupied Boston, a city of 16,000 colonists, to enforce Britain’s tax laws. British ships were at Boston Harbor and Nantasket Roads.

In 1773, the Tea Act granted the East India Company a monopoly on tea sales, reviving opposition. On December 16, 1773, American colonists disguised as Native Americans boarded British ships in Boston Harbor and dumped 342 chests of tea into the water.

In response, the British Parliament passed a series of laws known as the “Coercive Acts” (also called the “Intolerable Acts”), which closed the port of Boston and revoked the Massachusetts colony’s self-governing rights. The Boston Port Act, passed in March 1774, closed the Port to all commerce and ordered the citizens of Boston to pay a large fine to compensate for the tea thrown into the river during the Boston Tea Party. Responding to Patriot hostility, General Thomas Gage moved the colonial government from Boston to Salem on June 7, 1774, and outlawed unauthorized town meetings.

The General Court meeting in Salem refused to cooperate. Before he could shut it down, they voted to reconvene as County conventions “To Consider the Late Acts of Parliament.” The Essex County Convention met at Treadwell’s Inn in Ipswich and voted to approve the establishment of a Provincial Congress meeting in Concord. The resolutions concluded with “He can never die too soon who lays down his life in support of the laws and liberties of his country.”

While the Ipswich convention was meeting, on September 1, 1774, British soldiers, under orders from General Thomas Gage, marched to Charlestown and removed gunpowder from a Patriot magazine. The news spread like wildfire, and thousands of farmers and mechanics from the western communities put down their tools and became militiamen, streaming toward Boston. Loyalists and government officials were forced to seek protection in Boston with the British Army. The militia units dispersed and went back to their towns after learning that the Powder Alarm rumors were not true.

General Gage left Salem and returned to Boston. In the early morning of September 6, as Essex County representatives convened their meeting in Ipswich, over 4000 militiamen from 37 Worcester County towns marched on Worcester to shut down the courthouse to prevent the new Crown-appointed judges from taking their seats.

On Feb. 26, 1775, the Revolutionary War almost began in Salem. Military Governor Thomas Gage had returned to Boston and was informed that the “Minutemen” in Salem had collected the cannons and were arming themselves. Governor Gage sent Lieut. Col. Alexander Leslie with the 64th regiment by ship to Marblehead with instructions to march to Salem with 240 troops and seize the cannons and munitions. The alarm soon reached surrounding towns, where as many as 10,000 Minutemen prepared to join the fray. It ended peacefully with a compromise to allow Col Leslie and his troops to cross no more than fifty rods beyond the bridge and report to Gage that he hadn’t found anything.

On the night of April 19, 1775, the British Regulars marched on Lexington & Concord. Receiving the news the following morning in Ipswich, Capt. Nathaniel Wade’s company marched through the day without encountering the enemy and returned to Ipswich on the 21st. By April 24, up to 20,000 colonial rebels had holed up the British in Boston. The Provincial Congress, now meeting in Watertown, called for an army of 30,000 to maintain the siege at Boston. The Ipswich Company marched to Watertown and received orders from the Provincial Committee of Safety, assigning the company to a station in Cambridge.

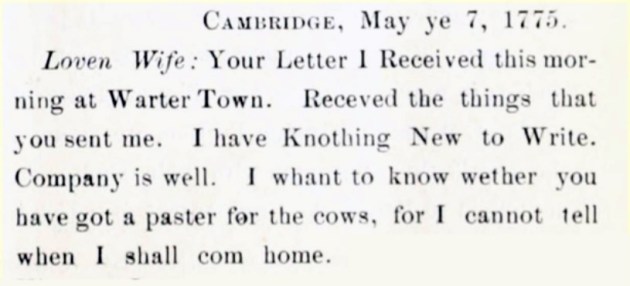

Ipswich volunteer Joseph Hodgkins signed articles of enlistment in the Provincial Service on January 24, 1775. Throughout the War, he sent letters home from the battlefronts to his wife, Sarah Perkins Hodgkins, longing for home and detailing the desperate troop conditions. From 1775 to 1778, Joseph wrote 86 letters; Sarah wrote twenty letters that survived, and at least 22 are known to have been lost. The original letters are physically stored in the Phillips Library Repository at the Peabody Essex Museum. Read the letters of Joseph Hodgkins and his wife, Sarah Perkins Hodgkins.

Throughout the spring, Essex County forces were encamped surrounding the British forces in Boston. The siege effectively cut off Boston from the countryside. Approximately 10,000 inhabitants fled the city within the first eight weeks, while hundreds of Loyalists sought refuge in the city.

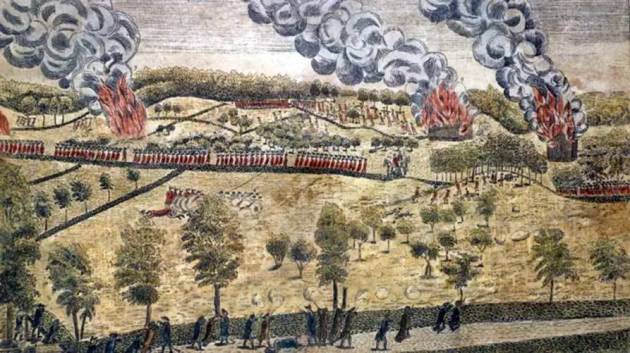

On June 13, 1775, 1200 colonial troops marched and began occupation of Bunker Hill and Breed’s Hill in Charlestown to prevent the British from occupying and fortifying the hills, which would give them control of Boston Harbor. Throughout the night, the colonial militias constructed a redoubt on Breed’s Hill.

On June 17, the British set Charlestown on fire, mounted three attacks on the Colonial forces, and were repulsed, resulting in significant casualties, but succeeded in a third attack when the defenders ran out of ammunition. The Colonists retreated, leaving the British in control of the peninsula. The British had 1054 casualties, and the colonists had 450.

Joseph Hodgkins wrote to Sarah, June 23, 1775: “We were preserved. I had one Ball that went under my arm and cut a large hole in my Coat & a buckshot went through my coat & Jacket, but neither of them did me any harm.”

In camp at Cambridge through the fall and winter of 1775, Joseph wrote to Sarah frequently. On Nov. 28, 1775, he wrote, “All is at stake and if we due not Exarte ourselves in this glorious Cause our all is gon and we are made slaves of for Ever.” On December 10, she wrote to him, “I look for you almost every day, but I don’t allow myself to depend on anything, for I find there is nothing to be depended upon but trouble & disappointments.”

“Give my regards to Capt. Wade, and tell I have wanted his bed fellow pretty much these cold nights that we have had.” (Excerpt from Sarah’s letter to Joseph, February 1, 1776)

“I gave your Regards to Capt. Wade, but he did not wish you had his Bed fellow. But I wish you had with all my heart.” (Excerpt from Joseph’s letter to Sarah, February 5, 1776)

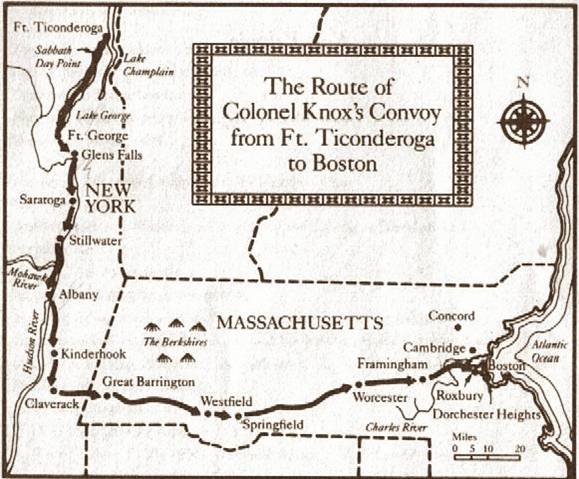

The British abandoned Fort Ticonderoga and Crown Point in November 1775 following the surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga. Henry Knox made an audacious proposal to General Washington. Why not retrieve the British cannons and artillery to Boston? The journey would be no easy feat. The Forts were hundreds of miles away, near Lake Champlain in New York. By then, it was winter.

Knox arrived at Fort Ticonderoga in early December 1775. He selected 58 mortars and cannons weighing at least 120,000 pounds. Knox planned to ship the cannons down Lake George before beginning the laborious trip overland: nearly 300 miles. Delivering the weapons to Boston required building new roads through the wilderness, but against all odds, Henry Knox, his men, and the weapons reached Washington’s army in mid-January 1776.

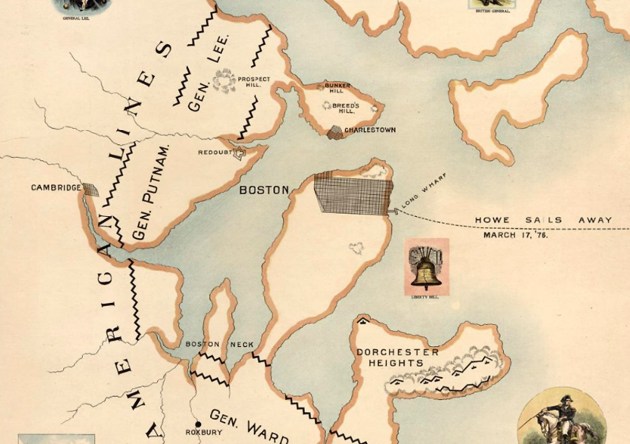

Acquiring the cannons from Ticonderoga changed the course of the war. Washington fortified Dorchester Heights, putting the British lines well within range of the new American cannons, and was determined to take the British by surprise. The cannons were dragged up the steep hill at Dorchester Heights quickly and in secrecy. Washington’s men managed the task in one night.

On the morning of March 5, 1776, the British awoke to American cannons staring down at them from the newly fortified Dorchester Heights. General William Howe, who had replaced General Gage as commander of the British forces occupying Boston, famously declared, “The rebels have done more in one night than my whole army would have done in a month.

The standoff dragged on for nearly two weeks before General Howe ordered the evacuation of Boston on March 16 after Howe and Washington reached an agreement that the British would not burn Boston as they left, and the colonials would not attack the British ships as they departed.

On March 17, 1776, the British finally evacuated Boston, accompanied by Loyalists who had fled to the city during the siege, and sailed to Halifax, Nova Scotia, restoring Boston to American control without a shot being fired from Dorchester Heights. Ironically, it’s the same day that we celebrate St. Patrick evacuating the snakes from Ireland!

On March 20, 1776 Joseph Hodgkins wrote to his wife Sarah, “My dear, there appeared a great movement among the enemy, and we soon found that they had left Bunker Hill & Boston, and all gone on board the shipping & our army took possession of Bunker Hill and also of Boston, but none went to Boston but those that have had the small pox. All I can say is that we must move somewhere very soon, but I would not have you make yourself uneasy about that, for our enemy seems to be fleeing before us, which seems to give a spring to our spirits.”

American forces surrounding Boston were kept in the dark about the Knox mission until Boston was secured. The war would continue for seven brutal years. Within three days, the Americans would begin marching to Providence.

Gravestone of Sarah Perkins Hodgkins. “Pass on, my friends, dry up your tears. Here I must lie till Christ appears. Death is a debt to nature due. I’ve paid the debt, and so must you.”