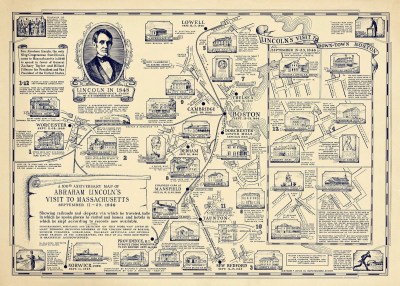

Abraham Lincoln toured New England twice. He never made it to Ipswich, but he did have some brushes with Essex County that influenced his development as a politician and his rise to the presidency. The first trip was as a sitting congressman in 1848, during which he gave ten speeches in Boston and outlying Massachusetts cities in defense of the Whig nominee for president, Zachary Taylor. The second trip was a dozen years later and led to eleven speeches spread across Rhode Island, southern New Hampshire, and Connecticut. By this time, he was a political celebrity, having gained notoriety from the Lincoln-Douglas Debates and the Cooper Union speech that immediately preceded his early 1860 visit. This article focuses primarily on the 1848 visit to the Bay State because it most directly relates to Ipswich and Essex County.

While Lincoln had served eight years in the Illinois State legislature and had become the Whig Party leader for the state, he was a small fish in the big ocean of the U.S. House of Representatives during his single term in that national institution. Freshman congressmen were expected to sit in the back of the room, keep their mouths shut, and vote the way the party told them. Lincoln chose instead to “distinguish” himself with a little speech demanding that Democratic President James K. Polk identify the exact spot where Mexican troops had crossed into U.S. territory, thus supposedly initiating the Mexican War. 1 While the speech would later be widely ridiculed and result in an ignominious nickname, “Spotty Lincoln,” it reflected the Whig belief that “the war was unnecessarily and unconstitutionally commenced by the President.” 2

Six months later, the Whigs bowed to public pressure and nominated the hero of that war as their party’s choice for president. As a good Whig and well-known for his entertaining speaking style, Lincoln was sent to Massachusetts in September of 1848 to campaign for Taylor. It was not an easy sell. Many Massachusetts Whigs found the hero for a war they “very generally opposed” objectionable. He was also a southern slaveholder, which convinced them the Whigs had lost their way. They voiced their objections with their feet, splitting off to form a new political entity, the Free Soil Party, focused on blocking the spread of slavery into the vast new territories just claimed from Mexico. 3

Reining in the wayward Free Soilers was the main task before Lincoln, arguing that the progressive Whigs were already fighting to keep slavery out of the territories and that a third-party vote would hand the election to the dreaded Democrats, the conservative party at the time. While he was traveling in Massachusetts giving speeches, however, the thirty-nine-year-old lawyer from the western frontier learned a lot about the realities of regional and national politics. As he later recalled, he “had been chosen to Congress then from the wild West, and with hayseed in my hair I went to Massachusetts to take a few lessons in deportment.” 4

He learned a few other lessons as well. Not only did he find some Whigs forming their own splinter party, but he found a growing divide between “Conscience Whigs” and “Cotton Whigs.” Conscience Whigs were those who felt strongly that slavery was wrong and needed to be put on a path toward its ultimate extinction. This group included many who joined the new party, but also across a wide spectrum based on how vehemently they pushed the anti-slavery issue. Some were more moderate, like Lincoln, focused on blocking expansion into the territories, while others were passionate abolitionists agitating for the immediate end of slavery everywhere in the nation, including the southern states where slavery had become entrenched. In contrast, the Cotton Whigs were so named because many were owners of the textile manufacturing factories that had grown steadily in the northeast. They were much less interested in abolitionist agitation, which gets to Lincoln’s first brush with Ipswich:

Lincoln traveled out to Lowell to speak at the Old City Hall, where one attendee described him as ungainly and homely, prone to humor to the point of appearing comical, “pronouncing words in a manner not usual in New England.” 5 His speech was generally well received, but he also had occasion to visit a textile mill and learn about the close relationship its owners had with the slave-grown cotton that provided the raw materials for their factory. In essence, Lowell typified the textile interests of the North, as well as its complicated complicity. 6

Prominent among these Cotton Whig mill owners were Francis Cabot Lowell (namesake of the city), the brothers Amos and Abbott Lawrence (namesakes of the city), and Nathan Appleton (relative of the Ipswich Appleton family), as well as Massachusetts Governor and polymath Edward Everett (later to give the 2-hour speech at Gettysburg no one remembers because of Lincon’s more concise Gettysburg Address) and perennial Whig leader Robert C. Winthrop (a direct descendant of John Winthrop the Younger, founder of Ipswich). 7 These men and others formed the Boston Associates, an informal monopoly in which forty families built dozens of cotton mills across New England, then expanded into a network of banking, insurance, and railroads to ensure control over all aspects of wealth generation. They declaimed abolitionist agitation as counterproductive to their lucrative cotton mill empires. 8 They were still Whigs, which meant they felt slavery was wrong and worked to keep it from spreading, but they made clear to their southern business partners they would block any attempt to abolish slavery in the states where it continued to exist.

But it was the son of Amos Lawrence, confusingly named Amos A. Lawrence (the “A” was for Adams, after the second and sixth presidents of the United States), who had the closest connection to Ipswich. Amos A. Lawrence purchased the town’s rudimentary textile mill and built it into the Ipswich Mills Company, which would go on to employ 1,500 people. In contrast to his father and uncle, this Lawrence grew into a leading advocate for abolition. And it was this Lawrence, who after a particularly egregious fugitive slave episode in Boston, wrote “we went to bed one night old fashioned, conservative, Compromise Union Whigs & waked up stark mad Abolitionists.” 9 Amos A. Lawrence chartered the New England Emigrant Aid Company in the 1850s to fund the westward movement of free-state settlers into the Kansas Territory in an attempt to establish Kansas as a free state without slavery. Despite their dependence on southern cotton, some of this new generation of wealthy textile industrialists would fund a zealot named John Brown, both in Kansas after the sacking of the free-state capital of Lawrence (named after this same Amos A. Lawrence) and at a small western Virginia town called Harpers Ferry. 10

Lincoln had another connection to Essex County in William Lloyd Garrison. The Newburyport native’s father had abandoned the family when Garrison was only three, leaving his mother to raise him under the strict religious morality that later drove his advocacy for Black freedom. He became apprenticed to a printer at age 13 and while having virtually no formal education, became so adept at it that he could compose writing directly as he typeset the Newburyport Free Press. Eventually, he moved to Boston and in 1831 started his own fervently antislavery newspaper, The Liberator.

Most antislavery advocates up to that time (including Abraham Lincoln) favored a gradual emancipation of enslaved people, often combined with some form of colonization outside the United States. The northern states had all ended slavery, mostly by gradual means. But while most felt slavery was immoral and wanted to see it end, there was not a strong push for equality of the races. White people had bought into the false concept that whites were a superior race, so the idea of living in political, economic, and social equality with formerly enslaved Black people was anathema to northern whites (and obviously even more overtly to southern whites). This incensed the fervently moralistic Garrison, who even other antislavery activists quickly labeled a raging radical.

In the very first issue of The Liberator, Garrison made his position on ending slavery now and forever clear:

On this subject, I do not wish to think, or to speak, or write, with moderation. No! no! Tell a man whose house is on fire to give a moderate alarm; tell him to moderately rescue his wife from the hands of the ravisher; tell the mother to gradually extricate her babe from the fire into which it has fallen; — but urge me not to use moderation in a cause like the present. I am in earnest — I will not equivocate — I will not excuse — I will not retreat a single inch — AND I WILL BE HEARD. The apathy of the people is enough to make every statue leap from its pedestal, and to hasten the resurrection of the dead. 11

As much as his fervor repelled some antislavery advocates, Garrison’s rhetoric encouraged a growing abolitionist sentiment in the North. That sentiment spread in the 1840s and then especially in the 1850s after the Fugitive Slave Act became law. Among those he inspired were Gerrit Smith, Wendell Phillips, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, and Theodore Parker, all of whom would later vacillate between enemies and allies of Lincoln. Phillips, for example, when Lincoln was later running for president, described 1848 Congressman Lincoln’s proposed bill to end slavery in the District of Columbia as “one of the poorest and most confused specimens of pro-slavery compromise.” Phillips doubled down by calling Lincoln “the slave-hound of Illinois” because that proposed bill (which he never formally introduced) included language to remove enslaved persons who might rush into the newly free capital from Maryland and Virginia, both slave states.

Lincoln began to understand the growth of this abolitionist fervor when he spoke in New Bedford. On September 14, 1848, he gave his Zachary Taylor campaign speech at Liberty Hall, known for its hosting of abolitionists, some of whom Lincoln would engage with in the future, not always favorably. As Lincoln rose to speak at Liberty Hall, he may have known that it was in this very hall seven years earlier that a newly escaped Frederick Douglass first heard firebrand abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison speak. 12 Lincoln had paid little attention to slavery up to this point in his career. Sure, as a young Illinois state legislator in 1837, he had dissented against a bill that criminalized “anti-slavery agitation.” But even there he explained that while “the institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy,” he thought abolitionism increased rather than abated its evils. He thought that while Congress could abolish slavery in the District of Columbia, it did not have the authority to interfere with slavery in the states where it was already present. Even during this tour of Massachusetts, he focused primarily on convincing Free Soilers that the Whig party was their best bet for blocking the expansion of slavery into the newly gained western territories. Neither the Whigs nor the Free Soilers were actively working to abolish slavery where it already existed. But it would have been hard to miss the abolitionist sentiment in New Bedford and at his other Massachusetts stops.

Garrison made no mention of Lincoln in the Liberator during his 1848 visit. After Lincoln was nominated as the Republican candidate for president in 1860, Garrison became a harsh critic of Lincoln and remained so right up until he issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, Now sensing some commitment to move toward abolition from President Lincoln, Garrison made a point to visit the White House and, unlike some other abolitionists (e.g., Wendell Phillips), strongly supported Lincoln’s 1864 reelection.

Another Essex County connection is none other than Frederick Douglass. Following his escape from slavery in Maryland, twenty-year-old Frederick Bailey made his way to New York, where he married and changed his last name to Johnson, then he was on to New Bedford, where he settled on the name we know him as today. 13 It was in New Bedford that Douglass first started reading Garrison’s The Liberator. Douglass later wrote that “My soul was set all on fire” by Garrison’s passionate call for the immediate abolishment of slavery and investiture of full equality. 14 Douglass would first see Garrison speak at Liberty Hall – the same one Lincoln spoke at – and it was Garrison’s people who asked Douglass for an impromptu recounting of his escape from slavery.

After several years in New Bedford, Douglass moved to Lynn, in Essex County, where he lived until his travels overseas and then on to Rochester, New York. Garrison and Douglass eventually had a falling out – Douglass came to believe more direct action was necessary, in contrast to Garrison’s moral fervor tempered by opposition to violence – but with Douglass’s speaking and Garrison’s adamant editorials, the two sparked a revolution in antislavery thought. Both men became dedicated supporters of Lincoln late in the Civil War despite his perceived slowness in issuing an emancipation order and his early stance on colonization.

Douglass, of course, would go on to have three famous meetings with President Lincoln during the war. Despite their different perspectives on the speed and degree of emancipation, the two men became respected friends. Douglass would go on to dedicate the Emancipation Memorial statue featuring Lincoln and a formerly enslaved man named Archer Alexander in Washington, DC on the centennial of the Declaration of Independence. Both Lincoln and Douglass believed in the eternal principle of the Declaration’s aspirational promise of “all men are created equal,” and worked to push the United States toward a more perfect Union. Unfortunately, it is an aspiration we struggle to achieve even today.

Also influential to Lincoln’s political growth were the female anti-slavery societies popping up in many Massachusetts towns. In Concord, Massachusetts, not only were transcendentalist writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Louisa May Alcott, and Henry David Thoreau influential, but also their wives, mothers, sisters, and other women. Even closer to home, the Ipswich Female Anti-Slavery Society was led by some of the wives and daughters of the more prominent scions of Ipswich.15 Women were not allowed in the all-male American Anti- Slavery Society, co-founded by William Lloyd Garrison, so persistent women in both Ipswich and Concord formed their own societies to fight the enslavement of fellow Americans. The Concord Female Antislavery Society coordinated with other such societies to bring speakers such as Garrison, Douglass, and even John Brown to towns of the northeast. Less publicized, but an open secret among like-minded townspeople, was that the Society helped run several Underground Railroad stations to facilitate the escape of enslaved Americans into Canada. The influence of these Massachusetts-based antislavery societies cannot be overestimated. While the men were making the headlines, it was these female antislavery organizations doing the grassroots work, inspiring local abolitionist sentiment and coordinating the escape routes for enslaved men, women, and children on the run. While it is unclear how much Lincoln was assimilating all of what was happening on his 1848 tour, he no doubt was hearing about these organizations and these inspirational writers from his Bay State hosts as he moved around the eastern part of the state. 16

Let me now jump ahead to Lincoln’s 1860 tour of New England. He traveled through Boston on his way from Providence to Exeter, New Hampshire, in late February of that year, and mentions taking the Boston & Maine Railroad. Most likely, the route took him through Lawrence since he later mentions in a letter to his wife Mary going through “the site of the Pemberton Mill tragedy” in that city as he moved around southern New Hampshire.

That letter to Mary, dated March 4, 1860, reveals a lot about Lincoln’s mental state during his New England visit. At the time he wrote it, he had already given six speeches (including Cooper Union) and was scheduled to give four more (he ended up giving six more). His original plan had been to give the one speech in New York, then take a leisurely trip to visit his son Robert, studying at Phillips Exeter Academy in preparation for retaking the Harvard entrance exams he failed the summer before. Lincoln was starting to feel the strain from the unexpected schedule: “I have been unable to escape this toil,” he wrote in his letter. “If I had foreseen it, I think I would not have come East at all.” He told Mary that the speech in New York “went off passably well, and gave me no trouble whatsoever.” But “the difficulty was to make nine others, before reading audiences, who have already seen all my ideas in print.” 17

Notwithstanding his exhausted complaints, the two trips to New England were incredibly important to his career development and to his nomination and election as president. In 1848, Lincoln was largely unknown in the East, and the little people did know was mostly that he was “a capital specimen of a ‘Sucker Whig’” who told jokes. 18 He was taken more for his entertainment value than he was as a serious policymaker by the more educated Whigs of New England, although his reputation also attracted larger numbers of working-class easterners (the Whigs were often considered an elitist party). By 1860, Lincoln had become famous. The Lincoln-Douglas debates had made him well known and now a viable political leader. On both trips, Lincoln was greeted with generally large crowds that grew in both size and enthusiasm with each stop. Whereas in 1848 he was campaigning for the already selected Whig nominee, the 1860 trip occurred three months before the new Republican Party held its nomination convention. Lincoln’s tour was setting both the ideological dynamic for the two major political parties and positioning himself as a viable candidate for the Republican nomination.

Indeed, since the nomination convention vote proceeded on an East to West basis starting with Maine, New England states gave Lincoln an unexpected boost on the first ballot, thus ensuring he was the overwhelming “second choice” to the presumptive nominee, New York senator William H. Seward. That early support, followed by shifts toward him on ensuing ballots, gave permission, in a sense, to other states to support Lincoln as the nominee. No doubt, Lincoln’s trips to Massachusetts and New England helped make him the nominee, and ultimately, the president.

[Ipswich native David J. Kent is an Abraham Lincoln historian who has written seven books. His newest book is Lincoln in New England: In Search of His Forgotten Tours.]

- Basler, Roy P. 1953. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (hereafter, Collected Works), Rutgers University Press, 1:431-442).

- Collected Works, 1:514.

- Ibid.

- Massachusetts Historical Society

- Collected Works, 2:6; Hanna, William F. 1983, Abraham Among the Yankees: Abraham Lincoln’s 1848 Visit to Massachusetts, The Old Colony Historical Society, Taunton, MA, 38-41; Hadley, Samuel P., 1909, “Recollections of Lincoln in Lowell in 1848 and Reading of Concluding Portion of the Emancipation Proclamation,” in The Abraham Lincoln Centennial, Lowell Historical Society, 370-372; Lowell Courier, September 18, 1848, 2; Boston Atlas, September 19, 1848, 2.

- Farrow, Anne, Lang, Joel, and Frank, Jenifer, 2005, Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited From Slavery, Ballantine Books. The insatiable need for more cotton production acreage was one impetus behind the 1830 Indian Removal Act that forced Native peoples known as the Five Civilized Tribes out of the mid-south into the barren land now largely the state of Oklahoma, then called “Indian Territory.”

- Farrow, Complicity; Burlingame, Michael, 2008, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Johns Hopkins University Press; Brauer, Kinley. 1967, Cotton Versus Conscience: Massachusetts Whig Politics and Southwestern Expansion, 1843-1848, Ross & Haines.

- Wilder, Craig Steven, 2013, Ebony & Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities, Bloomsbury Press, 285; Farrow, Complicity, 6, 25.

- Puleo, Stephen, 2012, The Caning: The Assault That Drove America to Civil War, Westholme Publishing, 38-39; McPherson, James M. 1988, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, Oxford University Press, 120.

- Puleo, The Caning, 6.

- See Massachusetts Historical Society Collections Online

- Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, 823; citing Pease, Zephaniah W., ed., The Diary of Samuel Rodman: A New Bedford Chronicle of Thirty-seven Years, 1821-1859, Reynolds, New Bedford, 287 (entry for September 15, 1848).

- Interestingly, Stephen A. Douglas originally was spelled with a second “s” but he dropped it the year after Frederick Douglass published his first autobiography; see Quitt, Martin H. 2012, Stephen A. Douglas and Antebellum Democracy, Cambridge University Press.

- Douglass, Frederick, 1855, Frederick Douglass: My Bondage and My Freedom, 90; Stewart, Matthew, 2024, An Emancipation of the Mind: Radical Philosophy, the War Over Slavery, and the Refounding of America, W.W. Norton, 7.

- Harris, Gordon, “Abolition and the Underground Railroad in Essex County,” Historic Ipswich

- Two months prior to Lincoln’s 1848 tour, Gerrit Smith’s cousin, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, led the convention in Seneca Falls, New York, fighting for women’s suffrage, so Lincoln may have been aware of this reform effort as well.

- Collected Works, 10:49-50. 18 Demaree, David, 2022, “A Stumping Sucker: Reception of Abraham Lincoln in Massachusetts, September 11- 23,1848,” Civil War History, 68(1):100.