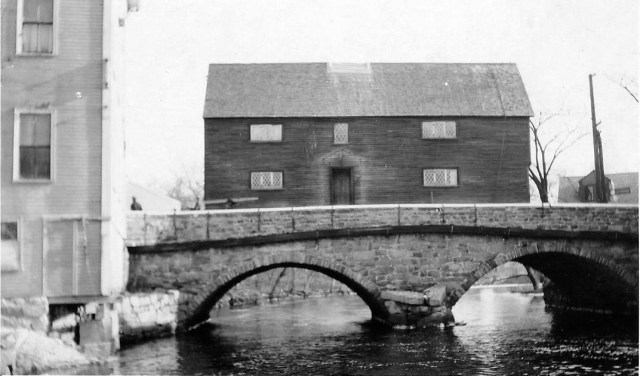

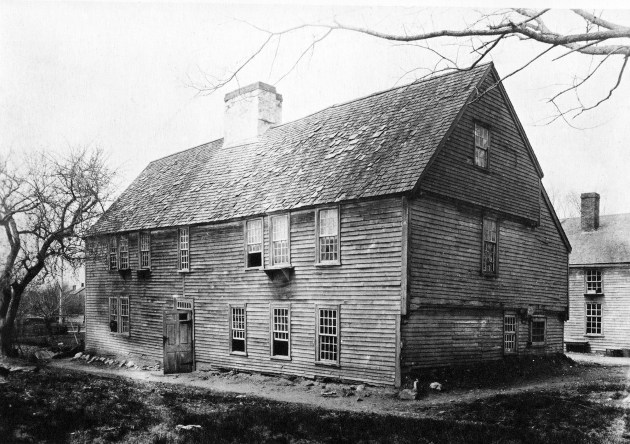

The 1677 Whipple House, owned by the Ipswich Museum, is a National Historic Landmark owned by the Ipswich Museum and is one of the finest examples of “first period” American architecture (1625-1725). The Ipswich Historical Society saved the house from destruction, restored it, and then moved it over the Choate Bridge to its present location in 1927. Today, the house’s frame of oak, chestnut, and tamarack is largely intact. Wall sheathing and clamshell ceiling plaster retain their first-period charm. Seventeenth and 18th-century furnishings and decorative arts by local and regional craftsmen fill the home.

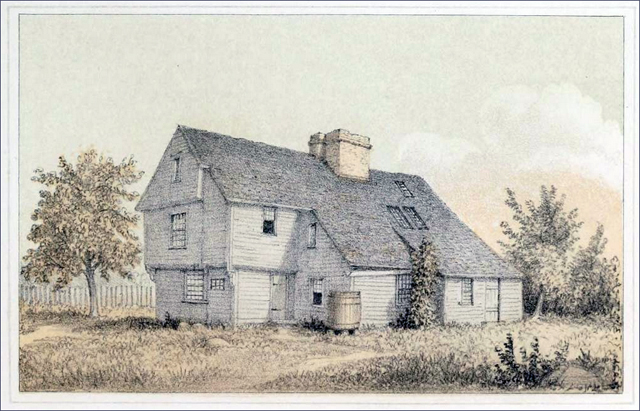

The oldest part of the house dates to 1677, when the military officer and entrepreneur Captain John Whipple constructed a townhouse on Saltonstall Street near the center of Ipswich. Before the 20th Century, oral history had attributed the house to John Fawne, who moved to Haverhill before 1638, and to Richard Saltonstall, the town’s first miller. Dendrochronology tests conducted in 2002 dated the oldest timbers in the house to 1677.

John Whipple’s son, Major John Whipple, doubled the size of the house by adding a lean-to addition in 1725 for slaves. The house was modified during the 18th Century with Georgian “improvements.” The Whipple House has the original frame, large fireplaces, summer beams, wide board floors, and gunstock posts. It was the home of Col. Joseph Hodgkins late in life after the Revolutionary War.

One of the earliest historic house museums in America, the Whipple House is a model in the early historic preservation movement thanks to the efforts of Rev. Thomas Franklin Waters, who saved the house during the Colonial Revival period. Tours of the Whipple House are available by inquiring at the Ipswich Museum.

Download “The Whipple House” as a PDF file, or read it online at Historic Ipswich.

The 1677 Whipple House is a National Historic Landmark owned by the Ipswich Museum and is one of the finest examples of “first period” American architecture (1625-1725). The oldest part of the house dates to 1677, when the military officer and entrepreneur Captain John Whipple constructed a townhouse on today’s Saltonstall Street. Before the 20th Century, oral history attributed the house to John Fawne, who moved to Haverhill before 1638, and to Richard Saltonstall, the town’s first miller. Dendrochronology tests conducted in 2002 dated the oldest timbers in the house to 1677. John Whipple’s son, Major John Whipple, doubled the size of the house and modified it with 18th-century Georgian improvements.

One of the earliest historic house museums in America, the Whipple House is a model in the early historic preservation movement thanks to the efforts of Rev. Thomas Franklin Waters, who saved the house during the Colonial Revival period. Tours of the Whipple House are available by inquiring at the Ipswich Museum.

The house had fallen into serious disrepair in the early 20th Century but was saved from destruction, and in 1927 was moved through town over the Choate Bridge to its current location facing the South Green, restored to its 1683 appearance. The original frame of oak, chestnut, and tamarack is largely intact. A colonial-style “housewife’s garden” greets visitors at the entrance.

The Whipple House has the original frame, large fireplaces, summer beams, wide board floors, and gun-stock posts. Originally at the corner of Market Street and Saltonstall Street, the Ipswich Historical Society saved the house from destruction, restored it, and then moved it over the Choate Bridge to its present location in 1927. Wall sheathing and clamshell ceiling plaster retain their first-period charm. Seventeenth and 18th-century furnishings and decorative arts by local and regional craftsmen fill the home.

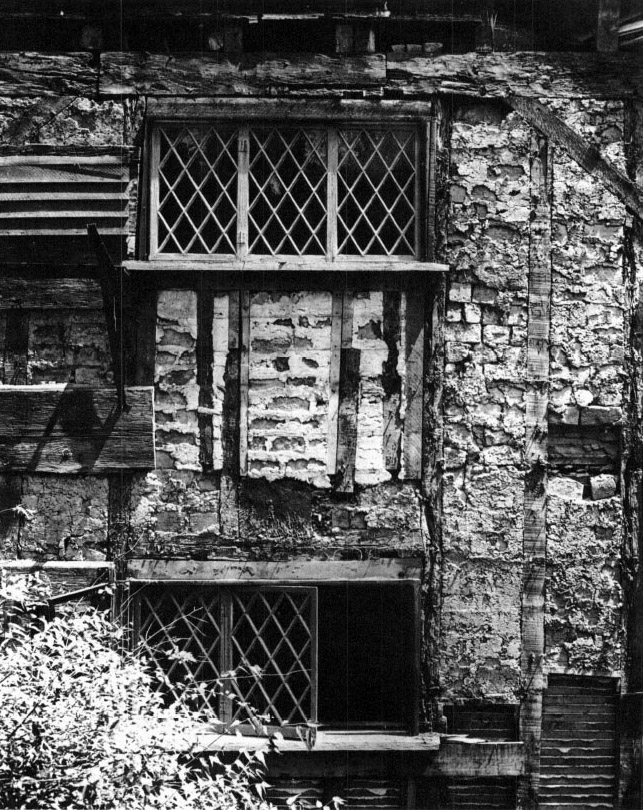

The Oxford Tree Ring Laboratory conducted research on the Whipple House and made the following findings: “Primary Phase Felling dates: Summer 1676, Winter 1676/7. Additional Felling dates: Summer 1689, Winter 1689/90. The Whipple House, which faces south, began as a single-cell house with a chimney bay on the east end. The original house, built in 1677, was two-and-one-half stories in height and featured a facade gable. In 1690, the house was enlarged by a substantial addition of twenty-four feet in length east of the chimney that included a second facade gable. Crossed summer beams in the east room suggest that the room was once partitioned along the transverse summer beam. The eastern part of the lean-to may have been constructed at the same time. On the east wall, both the main range and the lean-to were given hewn overhangs with substantial ogee moldings. The lean-to was later extended to the west and raised to two stories.”

Dendrochronology Report

WHIPPLE HOUSE, 53 South Main Street, Ipswich, Essex County, Massachusetts(42.677076, -70.836831)

In 2001-2002, the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (SPNEA), now called Historic New England, assisted by a Survey and Planning grant from the Massachusetts Historical Commission (MHC), undertook Phase II of the project to develop standard tree-ring chronologies for oak in Eastern Massachusetts. As part of the overall approach to the project, the undated material produced in 1975 from selected seventeenth-century buildings for SPNEA by Dr. William Robinson of the University of Arizona Tree-Ring Laboratory was reviewed. The Whipple House cores taken in 1975 have not been located, but the measurements are in the SPNEA files (*source)

Site Chronology Produced: ALC6 1480-1689. *Miles, D. H, Worthington, M. J., and Grady, A. A, 2002. “Development of Standard Tree-Ring Chronologies for Dating Historic Structures in Eastern Massachusetts Phase II”, Oxford Dendrochronology Laboratory unpublished report 2002/6

Felling dates: Summer 1676, Winter 1676/7 and Summer 1689, Winter 1689/90

Architectural Description: “The Whipple House, which faces south, began as a single-cell house with a chimney bay on the east end. The original house, built in 1677, was two-and-one-half stories in height and featured a facade gable. In 1690 (*corrected from 1790 on the report), the house was enlarged by a substantial addition, twenty-four feet in length east of the chimney that included a second facade gable. The crossed summer beams in the east room suggest that the room was originally partitioned along the transverse summer beam. The eastern part of the lean-to may have been constructed at the same time. On the east wall, both the main range and the lean-to were given hewn overhangs with substantial ogee moldings. The lean-to was later extended to the west and raised to two stories. Captain John Whipple (1625-1683), the second of three John Whipples who were prominent and wealthy Ipswich residents, built the original part of the house. His son, Major John Whipple (1657-1722) constructed the eastern part of the house six years after he inherited the house from his father. The house was purchased by the Ipswich Historical Society in 1898. In 1928, the house was moved to its present site, where it serves as a house museum.”

Wood is a good historian

The following story was written by the late John Fiske.

Wood is a good historian. The thought struck me as I was looking at a ceiling joist in the Whipple House.

In 1677, Capt John Whipple, a stalwart citizen of Ipswich, Massachusetts, built himself a two-story “half-house” (one room on each floor and a garret above). On the right-hand end was a huge stone hearth rising to a large chimney: in front of the hearth was the front door. Half-houses were the common starter homes of the time and were built with the full expectation that the other half, on the other side of the front door and the chimney, would be built as soon as the owner could afford to, or, at the very least, when his family outgrew the one-up, one-down with which he started.

Capt. John must have prospered quickly, or bred quickly, or both, because, by 1683, he had completed the second half, which he made slightly larger than the first. He added an extra flue to the chimney, and the line down the chimney shows us just where the half-house ended.

The first-floor room in the first half, known as the hall, was where all the physical work took place, from cooking to candle-making, from brewing to cheese-making to spinning. Its equivalent in the second half, however, (known as the parlor) was decidedly more genteel. Here, Whipple received his clients and did his accounts, here the family relaxed and entertained, and here Capt. John and his wife, and probably a child or two, slept in the only bed in the house – it was no good having as prestigious a piece of furniture as a bed if your neighbors and visitors couldn’t see it.

All this from looking at a ceiling joist? Well, not really, but it was a helpful background. You see, the joist had big vertical saw marks on its sides, and it was the only one in the parlor that did. On its underside, as with all the other joists, were irregular nail holes.

Now, I bet the housewright got an earful from Capt. John, about those saw marks. Smoothing tool marks out of wood was an expensive process, involving planing and then rubbing with an abrasive paste usually made of brick dust. The good Captain would not have wanted his clients and neighbors to think he couldn’t afford to have smooth joists in his ceiling.

But I was delighted that those saw marks had been overlooked, for they proved that Ipswich had a sawmill. The sawmill showed that the colony had outpaced the mother country and had set up a freer, more productive society. England had no sawmills as early as that; the sawyers’ guild (a trade union) was so powerful that it prevented their development to keep its members fully employed sawing wood over a deep pit with a pit saw. Pit saw marks are not vertical, but on an angle, because the underdog, the one in the pit, pulled the saw down and toward him on the cutting stroke. The guy on top, the top dog (yes, that is where those terms came from), merely guided the saw and pulled it up for the next downstroke. Topdogs get it easy – that’s a law of nature!

Capt John Whipple, then, was a member of a society that was developing as fast as it could – witness the sawmill and the speed with which he built the second half of his house. It was a forward-looking society where no ancient guild could restrict the freedom to cut wood in whichever way was most efficient.

Contrary to some assumptions, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was a strictly hierarchical society, and one of the functions of things in a hierarchy is to make rank visible. Capt John was a leading citizen, and it’s a modern misunderstanding to think of him as a show-off because he smoothed his joists. Smooth joists were one way of meeting his social obligation to make his rank visible.

But what about the holes on the joist’s underside? Much the same story. When Capt. John’s granddaughter, Mary Crocker, inherited the house. Visible joists, however smooth, had become lower class and old-fashioned, so she met her obligations to live in a house that visibly matched her status by hiding the joists behind a lath-and-plaster ceiling; hence the nail holes for the laths. An accurate match between things and rank stabilized the social order.

It has taken me quite a long time to put this story into words. A ceiling joist can tell it silently in half the time with twice the effect. More accurately to boot: there’s a photograph of this joist in Abbott Lowell Cummings’s definitive book, The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay, 1625-1725 (1979), but it is erroneously said to be in the 1677 half of the house. If you’re looking for history, go for wood, not words.

Slaves

The Whipple House was first owned by Captain John Whipple, whose estate was inventoried in 1669, and was not nearly so well off as his son afterward became. In addition to the townhouse, he had a farm of about 360 acres of land, worth $750, and houses and lands in the town, worth $1250, with $45 worth of “apparel,” $35 worth of “feather beds,” $6.75 worth of “chayres,” and $12 worth of “books.” Captain John Whipple Senior made his will in 1683. The extraordinarily detailed inventory of possessions in his will includes “Lawrence ye Indian at £4.”

There is an equally old Matthew Whipple house in Hamilton, which was formerly the Hamlet parish of Ipswich. The Hamilton Whipples had slaves, and a John Whipple of that branch of the Whipple family enslaved Jenny Slew, who was the first enslaved person to successfully sue for her freedom.

The Ipswich branch of the Whipple family also held people as slaves. Major John Whipple of the Whipple House in Ipswich was the eldest son of Captain John Whipple Senior. Thomas Franklin Waters wrote in “The History of the House“:

“When the Rev. John Rogers received for his son’s legacy, as his guardian, it is recorded that it was in accordance with the will of Major John Whipple.” It is important that every clue however slight to the successive generations of Whipples be noted, as we enter now a bewildering maze of John Whipple, Captain John, Major John, Cornet John, Elder John, John Senior, etc., through which it is very difficult to thread our way.

“This will of Major Whipple, drawn in 172,2 contains one item of note in determining the age of different portions of the house. It mentions the ” kitchen & Leanto.” One addition, at least, had been made prior to this date; but whether it was the very small leanto that seems to have been built on the northeast corner or the larger and later addition that provided a new kitchen, we cannot determine. I incline to the former hypothesis, as there is mention of only four rooms in the will and inventory. Two slaves are included in his estate, a negro man, who was given to Dame Crocker, and Hannah, who became the property of the minister’s wife, Mrs. John Rogers. We are glad that she (“My Negro woman Hannah”) was a person of sufficient note to be mentioned by name. The humble black man, who was sandwiched in between” an old common right and ‘Two Cowes,’ is mentioned only as a chattel.”

The Children of Matthew Whipple and Deacon John Whipple

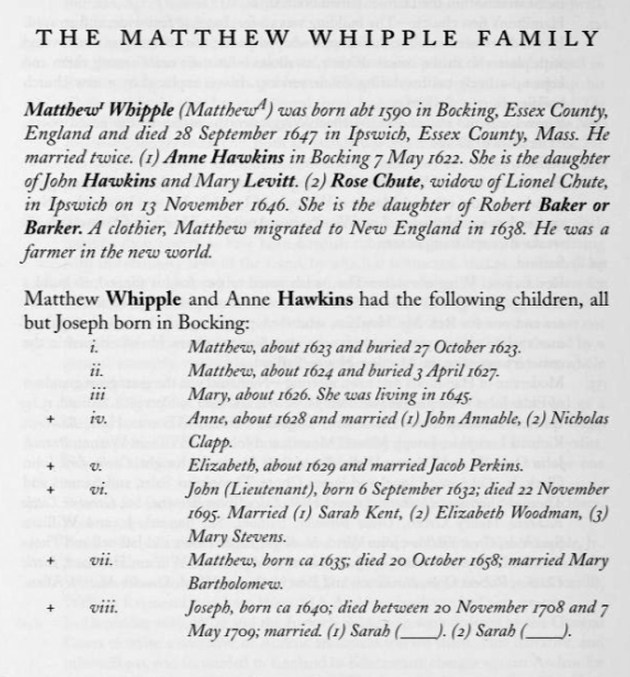

Matthew Whipple of Bocking (d.1618) had at least two sons, Matthew (c.1590–1647) and John (1596–1669), who came from Bocking, Essex, England to Ipswich.

(1) Matthew Whipple, born c.. 1590 in Bocking, Essex, England. Died 28 Sep 1647. Immigrated to Ipswich with his brother John. Married Anne Hawkins (his first wife). Their children:

- Matthew Whipple (c.1623 – Oct 1623). Died as an infant

- Matthew Whipple (c.1624 – 1627). Died as an infant

- Mary Whipple (1626-) *Some sources list her as Mary Ann and that she married James Readaway 1620-1676, and moved to Rehoboth, died in 1675. Unconfirmed.

- Anne Whipple (c.1628 – ?) married first, John Annable. Married second Nicholas Clapp.

- Elizabeth Whipple (c.1629 – 12 Feb 1684/5. Married Jacob Perkins

- Lieutenant John Whipple (6 Sep 1632 – 22 Nov 1695). Married 1st, Sarah Kent. Married 2nd Elizabeth Woodman. Married third, Mary Stevens.

- Matthew Whipple (c.1635 – 20 Oct 1658). Married Mary Bartholomew

- Joseph Whipple (c.1640 – c.1709. Married Sarah?

(2) Elder John Whipple, born Aug 1596 in Bocking, Essex, England. Died. 30 Jun 1669, Immigrated to Ipswich with his brother Matthew. Married Susanna Clark. Their children:

- Susanna Whipple (1 Jul 1622 – 10 Aug 1692). Married Lionel Worth in Ipswich

- John Whipple (1 Jan 1623/1624 – 4 Aug 1624). Infant, buried in Bocking

- Captain John Whipple (21 Dec 1625 – 10 Aug 1683). Constructed the Whipple House. Married (1) Martha Reynor, (2) Elizabeth Cogswell Paine, both of Ipswich

- Major John Whipple (1657–1722) eldest son of Captain John; he enlarged the Whipple House after 1683

- Elizabeth Whipple (1 Nov 1627 – 15 Dec 1648). Married Anthony Potter

- Matthew Whipple (7 Oct 1628 – 12 Oct 1634). Buried in Bocking.

- William Whipple (Oct 1631 – 4 Jun 1641). Buried in Ipswich

- Anne Whipple (2 Jun 1633 – 4 May 1634). Buried in Bocking

- Mary Whipple (2 Feb 1634 –2 June 1720). Married Simon Stone in Watertown.

- Matthew (17 Feb-Mar 1637) Died in Bocking

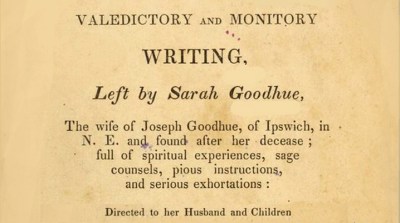

- Sarah Whipple (1641 -1681) married Joseph Goodhue. Wrote a Valedictory before her death.

Sources and further reading

- History of the House by Thomas Franklin Waters

- Report on the Committee on Repairs

- Ipswich Museum: Whipple House

- The John Whipple House by the Ipswich Historical Society

- A Hotel Cluny of a New England Village by Sylvester Baxter, A study presented by W. H. Downes to the Ipswich Historical Society, 1899

- History and genealogy of “Elder” John Whipple of Ipswich, Massachusetts: his English ancestors and American descendants

- Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Vol. 1 (Whipple search)

- Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Vol. 2 (Whipple search)

- Wikipedia: Maj. John Whipple House

- History and Genealogy of Elder John Whipple of Ipswich, Massachusetts

- Hammatt, Abraham: Early Inhabitants of Ipswich

- Sarah Goodhue’s Advance Directive, July 14, 1681

- Matthew Whipple of Ipswich, Massachusetts, abt. 1590-1647: Vol. 1

- John Whipple

- Matthew Whipple, 1590-1647

- Whipple, Blaine: Fifteen Generations of Whipples, Descendants of Matthew Whipple of Ipswich

- Whipple, Blaine: History and Genealogy of “Elder JohnWhipple of Ipswich

- Publications of the Ipswich Historical Society

- VI Dedication of the Ancient House or read at Google Books or at Hathi Trust Full view v.1-6 1894-1899

- X The History of the (Whipple) House or at Hathi Trust Full view v. 8-15

- X The John Whipple House and the People Who Have Owned It or at Hathi Trust Full view v. 8-15

- XX The John Whipple House or Read at Google Books or at Hathi Trust Full view no.16-20(1909-1915)

Related Posts

The Ipswich Visitor Center - 1820 Hall-Haskell House sits at the heart of our town on the Center Green, in one of several national historic districts in town.… Continue reading The Ipswich Visitor Center

The Ipswich Visitor Center - 1820 Hall-Haskell House sits at the heart of our town on the Center Green, in one of several national historic districts in town.… Continue reading The Ipswich Visitor Center  South Green Historic District - The South Green dates from 1686, when the town voted that the area be held in common, and became known as the School House Green. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. … Continue reading South Green Historic District

South Green Historic District - The South Green dates from 1686, when the town voted that the area be held in common, and became known as the School House Green. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. … Continue reading South Green Historic District  Ipswich Listings in the National Register of Historic Places - Authorized by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the National Register of Historic Places supports public and private efforts to identify, and protect America's historic and archeological resources.… Continue reading Ipswich Listings in the National Register of Historic Places

Ipswich Listings in the National Register of Historic Places - Authorized by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the National Register of Historic Places supports public and private efforts to identify, and protect America's historic and archeological resources.… Continue reading Ipswich Listings in the National Register of Historic Places  First Period Construction - 17th Century construction methods in New England were derived from English post-medieval carpentry traditions. Eastern Massachusetts contains the greatest concentration of First Period structures in the nation. … Continue reading First Period Construction

First Period Construction - 17th Century construction methods in New England were derived from English post-medieval carpentry traditions. Eastern Massachusetts contains the greatest concentration of First Period structures in the nation. … Continue reading First Period Construction  54 S. Main St., the Heard House / Ipswich Museum (1795) - The Museum provides tours of the First Period Whipple House and works by nineteenth-century Ipswich Painters including Arthur Wesley Dow. … Continue reading 54 S. Main St., the Heard House / Ipswich Museum (1795)

54 S. Main St., the Heard House / Ipswich Museum (1795) - The Museum provides tours of the First Period Whipple House and works by nineteenth-century Ipswich Painters including Arthur Wesley Dow. … Continue reading 54 S. Main St., the Heard House / Ipswich Museum (1795)  3 Candlewood Rd., the Brown-Whipple House (1812) - Joseph Brown built this house in 1812 as a dwelling for his son, James, and sold him the house and 3 acres, Dec. 23, 1817. The entire estate of Joseph Brown eventually was inherited by James. In 1852, D. F. Brown and the other heirs sold their interest to Hervey Whipple, who had married Martha P., daughter of James Brown, July 3, 1852. The heirs of Hervey Whipple still occupied into the 21st Century. … Continue reading 3 Candlewood Rd., the Brown-Whipple House (1812)

3 Candlewood Rd., the Brown-Whipple House (1812) - Joseph Brown built this house in 1812 as a dwelling for his son, James, and sold him the house and 3 acres, Dec. 23, 1817. The entire estate of Joseph Brown eventually was inherited by James. In 1852, D. F. Brown and the other heirs sold their interest to Hervey Whipple, who had married Martha P., daughter of James Brown, July 3, 1852. The heirs of Hervey Whipple still occupied into the 21st Century. … Continue reading 3 Candlewood Rd., the Brown-Whipple House (1812)  1 South Green, the Captain John Whipple House (1677/1690) - The oldest part of the house dates to 1677 when Captain John Whipple constructed a townhouse near the center of Ipswich. In 1927 the Historical Society moved it over the Choate Bridge to its current location and restored to its original appearance.

… Continue reading 1 South Green, the Captain John Whipple House (1677/1690)

1 South Green, the Captain John Whipple House (1677/1690) - The oldest part of the house dates to 1677 when Captain John Whipple constructed a townhouse near the center of Ipswich. In 1927 the Historical Society moved it over the Choate Bridge to its current location and restored to its original appearance.

… Continue reading 1 South Green, the Captain John Whipple House (1677/1690)  The Alexander Knight House - In 1648, Alexander Knight was charged with the death of his chiled whose clothes caught on fire. A jury fined him for carelessness after being warned. The town took mercy and voted to provide him a piece of land "whereas Alexander Knight is altogether destitute, his wife alsoe neare her tyme."… Continue reading The Alexander Knight House

The Alexander Knight House - In 1648, Alexander Knight was charged with the death of his chiled whose clothes caught on fire. A jury fined him for carelessness after being warned. The town took mercy and voted to provide him a piece of land "whereas Alexander Knight is altogether destitute, his wife alsoe neare her tyme."… Continue reading The Alexander Knight House  Sarah Goodhue’s Advance Directive, July 14, 1681 - On July 14, 1681, Sarah Whipple Goodhue left a note to her husband that read: "Dear husband, if by sudden death I am taken away from thee, there is infolded among thy papers something that I have to say to thee and others." She died three days after bearing twins. This is the letter to her husband and children.… Continue reading Sarah Goodhue’s Advance Directive, July 14, 1681

Sarah Goodhue’s Advance Directive, July 14, 1681 - On July 14, 1681, Sarah Whipple Goodhue left a note to her husband that read: "Dear husband, if by sudden death I am taken away from thee, there is infolded among thy papers something that I have to say to thee and others." She died three days after bearing twins. This is the letter to her husband and children.… Continue reading Sarah Goodhue’s Advance Directive, July 14, 1681  Early American Gardens - Isadore Smith (1902-1985) lived on Argilla Road in Ipswich and was the author of 3 volumes about 17th-19th Century gardens, writing under the pseudonym Ann Leighton. As a member of the Ipswich Garden Club, she created a traditional seventeenth century rose garden at the Whipple House.… Continue reading Early American Gardens

Early American Gardens - Isadore Smith (1902-1985) lived on Argilla Road in Ipswich and was the author of 3 volumes about 17th-19th Century gardens, writing under the pseudonym Ann Leighton. As a member of the Ipswich Garden Club, she created a traditional seventeenth century rose garden at the Whipple House.… Continue reading Early American Gardens

John Whipple Sr. is my 11th Great Uncle. His brother Matthew who he immigrated here with in 1638 is my 11th Great Grandfather. I am so thrilled to see a piece of my family history preserved. I love it. Thank you.

Wonderful to hear all this information about the Whipple House. It’s been a favorite of mine for many years in Ipswich. It’s amazing to hear the history of early settlements. Thank you.

Isadore Smith (Ann Leighton) researched and created the 17th C Housewife’s Garden of medicinal and household herbs.

The Old Rose (pre 1864 varieties) Garden was created by Margaret Austin of Ipswich and Elizabeth Newton who was curator of the Ipswich Historical Society. Although Mrs. Smith requested Mrs. Austin create the garden, Mrs. Smith had no part in researching or collecting the roses.

This is an amazing peice of information. The house was built with such elegance and beauty. What fascinates me the most is that Captian John Whipple was my 16th great grandfather and one day I wish to visit his home as inspire me as he did in the town .