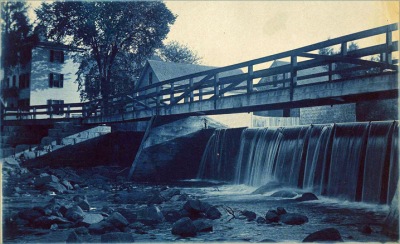

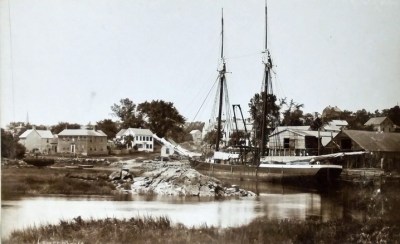

Featured image: Cyanotype of the Ipswich Mills Dam and footbridge, circa 1910 by Arthur Wesley Dow.

You can download this article as a PDF file.

This Towne is scituated on a faire and delightful river, whose first rise or spring begins about twenty-five miles farther up the country, issuing forth a very pleasant pond. But soon after it betakes its course through a most hideous swamp of large extent, even for many miles, being a great harbour for bears. After its coming forth this place, it groweth larger by the income of many small rivers, and issues forth in the sea, due east against the Island of Sholes, a great place of fishing for our English nation.”

–Capt. Edward Johnson, in his 1646 Wonder Working Providence”

Before the first dam was built on the Ipswich River, there were two sets of natural waterfalls in Ipswich that are referred to as the Upper and Lower Falls. The first of several small crib dams was built in 1637 on the upper falls, approximately 30 feet above today’s Ipswich Mills Dam. The remains of an early dam were visible during the drawdown of water behind the dam in August 2016. The current dam dates to the late 19th century and was modified in 1908, increasing its height and structural design.

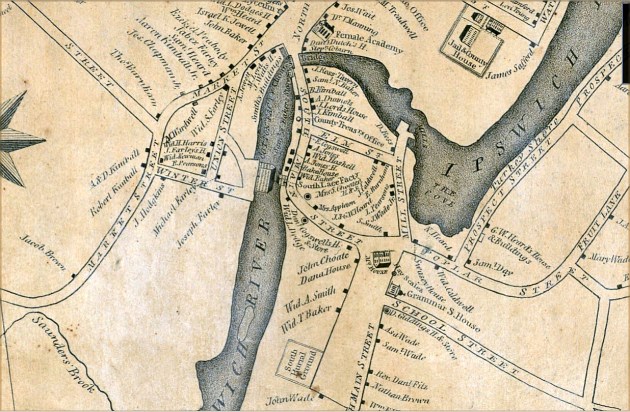

The swampy lot on which the Ipswich mill and dam are situated was granted to Richard Saltonstall in 1635 for the site of a grist mill. The area around the dam came to be known as the “Mill Garden,” with a ford below the dam. The grist mill was operated for many years by Michael and Mesheck Farley, after which the Farley family purchased the mill, with descendants of Richard Saltonstall continuing to hold a financial interest. In 1657, a hemp mill was established for making rope, followed by fulling mills, dye houses, sawmills, bark mills, tanneries, a scythe mill, and a sawmill on the south side of the dam in 1729, which was still in operation in 1792 under the management of Asa Andrews.

In 167,4 Nathaniel Rust and Samuel Hunt were permitted to construct a weir at the mill dam, “provided it does not hinder the mill or the passage thereto.” The two stone walls of the weir were constructed downstream at 45 degrees to each other, coming close enough together to drive fish into cages “in great numbers.”

In the early 19th century, George Heard purchased the Dr. Philemon Dean House on South Main Street and constructed an addition in which lace machinery was installed. The operation was transferred to the Boston and Ipswich Lace Co., consisting of Joseph Farley, William H. Sumner, Augustine Heard, and George W. Heard on Feb. 4, 1824, but the company became insolvent, and the factory was sold at auction in 1827 to Theodore Andrews.

The Ipswich Manufacturing Company was incorporated on June 11, 1828, by Joseph Farley, Augustine Heard, and George W. Heard. The first substantial stone dam was built over the ancient ford with the Town’s permission, and a large stone mill was erected at great expense for the manufacture of cotton cloth. The height of the “mill pond” behind the dam was raised and lowered by wooden flashboards. By 1832, the mill had 3000 spindles and 260 looms.

The middle of the 19th century saw continued growth in the town’s textile industries, and in 1863, a large mill was constructed on County Street adjacent to the lower falls. In 1843, Benjamin Hoyt constructed a new sawmill at the upper dam location, which continued in operation for fifteen years, when the building was moved to 17 County Street, where it was used for a shoe factory, but is now a private residence.

In 1846, the Dane Manufacturing Company purchased the stone mill for $24,000 to manufacture drill, a coarse cotton cloth. Amos Lawrence purchased the mill and dam in January 1868 and began the production of hosiery as the Ipswich Mills Company, which became the largest stocking mill in the country. When the flashboards were raised to a height of 18” in 1858, properties upstream of the dam were flooded, and the mill had to compensate upstream owners for the loss of their land.

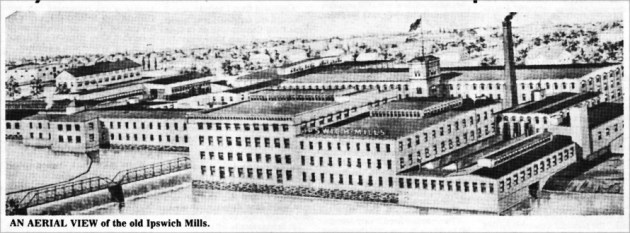

For many years, the Ipswich Mills Corporation was the chief industrial enterprise of the Town, bringing with it an era of prosperity. At the Ipswich mill, there were 1500 employees, of whom seventy-five percent were female. Each week, 55,000 dozen pairs of hosiery were produced, with an annual output of nearly four million dozen pairs. During this period, the population of Ipswich doubled with the influx of foreign workers in the mills. A prolonged strike in 1913 by foreign-born workers resulted in the shooting death of a young Greek woman, Nicoletta Paudelopoulou, by the police.

The use of water power to power machinery in New England textile mills was replaced by steam in the second half of the 19th Century. Electrical machinery was added early in the 20th Century, and for over 100 years the dam has no longer served its intended purpose. The Ipswich Mills continued in operation until it closed in 1928 after failing to keep up with the latest hosiery fashions. In 1941 Sylvania purchased the dam and the mill buildings for the production of transformers, tungsten coils, and the secret production of proximity fuzes during World War II.

In 1982, the Town of Ipswich purchased the dam from GTE Sylvania, and the Ipswich Utilities Department became responsible for its maintenance. EBSCO Publishing bought the mill in 1995 from Osram Sylvania and succeeded in placing the buildings and the neighboring worker housing known as “Pole Alley” on the National Register of Historic Places. The mill dam has never been nominated for the National Register. EBSCO continues to base its operations out of the old mill facility, although the introduction of remote working during the COVID-19 epidemic has greatly reduced the number of personnel working on-site.

The Natural History of the Ipswich River

The Ipswich Historical Commission was established in 1964 under the aegis of Massachusetts General Law (M.G.L.) Chapter 40, Section 8D “for the preservation, protection, and development of the historical or archeological assets of such city or town.” When considering the proposed removal of the Ipswich Mills Dam, it helps to think about the Ipswich River’s history holistically. The construction of dams and the loss of flow in the Ipswich River resulted in its once-great diversity of fish being reduced to a few generalist species that are found in lake and river environments.

The present Ipswich Mills Dam has existed for only a fraction of the history of the Ipswich River, although geologically, the river is quite young. The Laurentide ice sheet from the most recent ice age receded to the northern border of Massachusetts around 14,000 years ago. As the ice melted, the sea level rose about 100 ft. higher than current levels, putting much of the North Shore area temporarily under water until the land, which had been lowered by the weight of the glaciers, began to rebound about 12,000 years ago. The drumlins, moraines, and eskers that the glaciers left behind dictate much of the course of the river as it winds its way from Wilmington until it encounters the foot of Town Hill in Ipswich. From there, the river follows a minor geological fault past the Town Landing and enters the ocean between two glacial drumlins, Little Neck and Steep Hill.

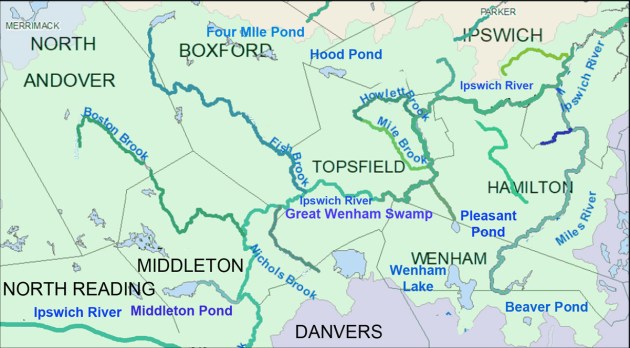

The average river slope is 3.1 ft/mi, but slopes range from about 6.0 ft/mi in the headwaters to 1.5 ft/mi in the middle reaches to 2.8 ft/mi in the lower third of the river. The gradient of the main channel is further decreased by three dams—the South Middleton Dam in Middleton, the Willowdale Dam in Ipswich/Hamilton, and the Sylvania (EBSCP) Dam in Ipswich (*Assessment of Habitat, Fish Communities, and Streamflow Requirements for Habitat Protection, Ipswich River, Massachusetts, 1998–99)

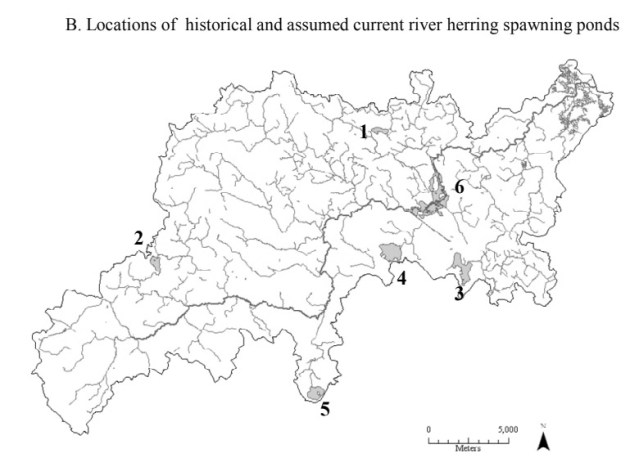

The Ipswich River watershed is 148 square miles and includes all or part of 21 communities. Until the 17th Century, the river ran unencumbered by man-made dams from its origin 35 miles upstream. In the spring, blueback herring, shad, salmon, and alewife swam upstream to spawn at the Great Wenham Swamp and numerous ponds and tributaries. The Ipswich River Watershed today includes Hood Pond in Topsfield; Lowe Pond, Spofford Pond, and Four Mile Pond in Boxford via Pye Brook and Howlett Brook; and Wenham Lake via the Miles River. The anadromous fishery was extremely productive and also included smelt, American eels, sea run trout, and sturgeon during colonial times.

Over a million alewives swam upstream to Wenham Lake as late as the 1890s. The freshwater lakes, ponds, streams, and the river were a cornucopia of large and smallmouth bass, red perch, yellow perch, white perch, pickerel, catfish, and black bass, foraging on what once seemed like an unlimited supply of herring. The dramatic lowering of the water level on the Miles River in the 20th Century ended spawning at Wenham Lake and other ponds along its course. What is left of the lake’s outlet, Alewife Brook, trickles through a culvert underneath Rt. 1A in Wenham. During the 2006 Mother’s Day storm, over ten inches of rain fell, and Wenham Lake overflowed its banks because the culvert to Alewife Brook quickly filled with debris.

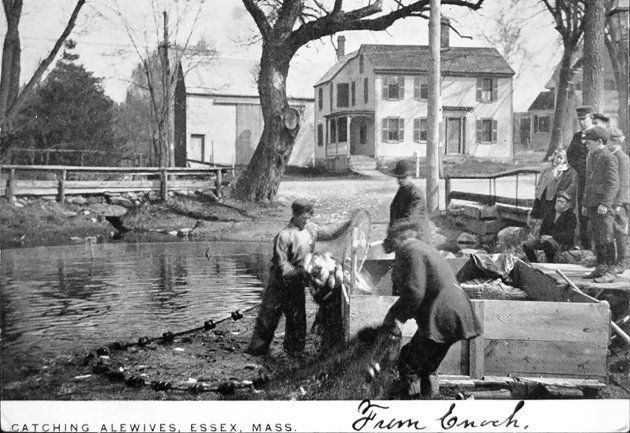

Young alewives imprint during their freshwater residency, and upon reaching an approximate size of 4”, return from the breeding grounds via the Ipswich River to the ocean, where their arrival is anticipated as food by numerous saltwater species, including Atlantic cod, halibut, and striped bass. Alewives that survive return as adult fish to the same rivers for spawning. Indigenous Peoples depended on these fish as a supply of animal protein and caught alewives by building weirs constructed of sticks and brush to force the fish into narrow channels, where they could be easily netted. At the Plymouth colony, only half of the 102 Pilgrims survived the first winter, but river herring making their annual return in the spring provided the survivors a rich bounty of food.

In 1709, a Massachusetts act was passed for the prevention of all obstructions to the passage of fish in rivers, except mill dams. An act in 1735 required dam owners to provide a “convenient sluice or passage” for alewives from the first day of April to the last day of May annually, and that the owners of the dams be required to allow a sufficient water flow for the young to pass back down. Historian Joseph Felt wrote that in 1747, a passage was made in two Ipswich mill dams for the alewives. Catching alewives in any other manner than prescribed by the town brought a penalty of ten shillings for each offense.

Yet in 1745, Massachusetts mill owners exerted political pressure to pass a provision abolishing fishways where the fish did not pass upstream in sufficient numbers to be of greater benefit than the damage from loss of water power due to the opening of the dam. But in 1770, Chapter 6 of the Province Laws was passed by the State to prevent the destruction of Alewives and fish in the Ipswich River, requiring dams to maintain a passage for fish during the migratory period from late April to mid-June.

As the various species of herring passed in shoals over the fishways of the 18th and 19th centuries, they were seined at night by the light of torches under the arches of the Choate Bridge, and great quantities were taken with dip nets by fishermen lined up in dories at the dam. By the 1800s, the annual catch averaged 350 barrels, much of which went to the West Indies.

In late summer and fall, as the young herring began their migration out to sea, men would be in boats all along the river for “herringing” by torchlight. At the Summer Street landing, herring were delivered from the boats’ hatches by buckets, with fishermen receiving $1 per bucket. In later years, the fish were sucked into trucks by long hoses directly from the boats. Another way to catch herring was circling and rounding up the fish with seine nets. William J. Barton wrote, “One year, there were so many herring caught that they were sold to people with large farms, such as Castle Hill, and 1000 barrels were put on the land for fertilizer. This same year, far too many herring were caught that could not be sold and were dumped in the Parker River. Herring did not return for many years.”

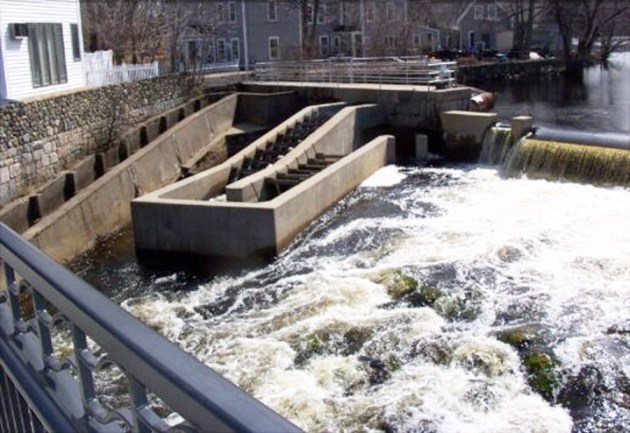

The present Ipswich Mills Dam is believed to have been constructed and reconstructed by Amos Lawrence during the period from 1880 to 1908. Each stone measures 6 feet wide x 20 inches tall x four feet deep, weighing approximately 5,000 lbs. At six feet tall, the present dam exceeds the maximum height that spawning fish can jump. The construction of two fish ladders has had minimal effect, and the great migration of fish along the river has all but ended. The mill dam alters the river in both directions by impeding the movement of fish and animals. It also reduces the amount of dissolved oxygen upstream in the mill pond, making it inhospitable to aquatic species and spawning fish. In addition to the obstruction created by the dam, biologists at the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries point to low flow as an impediment in restoring a successful river herring population in the Ipswich River. Despite Alewives having been stocked in the Ipswich River since 2003, annual fish counts during the spring herring run have remained low, ranging from an estimated 98-420 adults per year.

Historically, the Ipswich River supported an annual run of both species of river herring, Alewife and Blueback Herring, with a commercial fishery exporting thousands of barrels of fish annually. One of the largest historic alewife spawning habitats in the Ipswich River watershed is the Great Wenham Swamp, an extensive wetland covering 2.5 square miles. Between it and the River is the Grand Wenham Canal, which was completed in 1917 under a Massachusetts “Act to Provide an Additional Water Supply for the Cities of Salem and Beverly” and diverts millions of gallons of water from the Ipswich River from December through May to Wenham Lake to supply water to Beverly and Salem.

In thinking about the future of the Ipswich Mills Dam, not only are there thousands of years of history but there is also the future history we create. Removal of the dam will provide the opportunity to restore the Upper Falls and the early ford that disappeared in the 19th century to establish a level footing for the dam. Thirty feet behind the mill dam, a 17th or 18th-century crib dam will reappear. Water levels immediately upstream from the dam will average an estimated three feet lower, restoring the natural floodplain that can mitigate floods such as the Mother’s Day Flood we experienced in 2006. The homing migrations of the alewife will be an annual attraction for residents and tourists, congregating on the Choate Bridge and the Riverwalk pedestrian bridge for the annual display of herring swimming upriver.

Perhaps we will see an increase in beaver activity in the river above the mill. It is estimated that there were as many as 400,000 beavers in the continental United States before Europeans and their Native American partners hunted them almost to extinction. Unlike man-made dams, beaver dams are not usually a serious impediment to the annual run of anadromous fish. The vast network of dams and wetlands created by beavers greatly reduces the impact of floods and provides habitat for great blue herons, wood ducks, tree swallows, fish, amphibians, turtles, otters, muskrats, and other animals. When beavers exhaust their food supply and move to a new location, the pond drains, creating rich “beaver meadows” and habitat for a new cycle of trees and other vegetation. Pre-colonial beaver meadows were utilized as planting grounds by settlers because of their rich soil. Studies have shown that river sediment loads decrease by as much as 90% in areas with well-developed riparian habitats and beaver dams. Without beavers, there would be fewer wetlands, less successional forests in our open spaces, worse water quality, and less water in our aquifers. In a time when we are concerned about over-development, beavers are our natural allies.

The loss of forest land and riverine habitat in our more urban neighboring towns and cities prevents restocking of the herring in those locations. But the Town of Ipswich is fortunate that much of the forested area upstream from the Ipswich River is protected from development by Bradley Palmer State Park, Willowdale State Forest, Mass Audubon’s Ipswich River Sanctuary, and Harold Parker State Forest. Without forests, rainfall is not absorbed by the ground and passes quickly into the streams, causing erosion and heavy freshets. Correspondingly, the Ipswich River and its 150 square mile watershed, with its network of contributing streams, lakes, ponds, and wetlands, is the reason these protected areas survive.

It may come as a surprise to learn that below the dam are additional tributaries to the Ipswich River. Underneath High Street and Central Street are pipes for small streams draining from Town Hill. With the development of the railroad and steam machinery in the 19th Century, the large expanse of wetland around Farley’s Brook in the center of Ipswich was trenched, drained, and filled. Streams were forced underground in culverts, and new buildings, houses, and roads were constructed to create today’s downtown.

Dams on the Ipswich River at the lower falls and at the Warner stone arch bridge on Mill Road were removed by the late 19th Century, and the dam at Foote Brothers on Topsfield Road is scheduled to receive a new fishway. An absence of fishways, even on small dams, decimates anadromous fish migrations. The Massachusetts Division of Ecological Restoration ranks the Ipswich Mills head-of-tide dam in the top 5% of all dams in Massachusetts for removal, as it would open 49.19 miles of riverine freshwater habitat for restoration.

On the north side of Ipswich, the Bull Brook/Egypt River system was a historically active migratory and spawning pathway for rainbow smelt, alewife, blueback herring, and white perch. The two dams that create the Bull Brook and Dow Brook Reservoirs were constructed with no fish ladders, and prohibit fish passage to and from the Egypt River. In 1965, the town of Ipswich constructed a half-acre pond with a fishway at the site of the old municipal electrical generating plant, which has demonstrated success as a small spawning area for alewives.

In the towns of Essex and Hamilton, which were both part of Ipswich until the 19th Century, Chebacco Lake drains into Alewife Brook, which becomes the Essex River. It is one of the few Massachusetts herring runs without a man-made dam, although silting, plant growth, and beaver dams have impacted spawning.

in the Ipswich River“.

Blueback herring, which spawn in mainstem rivers, enjoy about 30 miles of excellent habitat on the Ipswich River. Shad prefers shallow water, and the fish has about 15 miles of suitable habitat between the Willowdale Dam and Middleton. Full restoration for some androgynous fish will rely on the restoration of upriver riverine environments. Seasonal flow conditions are a limiting factor for the herring population in the Ipswich River, which must provide adequate nursery habitat for both the early life stages to thrive, and for juveniles to emigrate, but herring are known to adapt their timing to drought conditions. The 3-4-year life cycles of blueback herrings and alewives provide multiple years for the successful reproduction of the species.

With all anadromous fish, migratory success will be greatly improved by the removal of the Ipswich Mills Dam. It is hoped that successful dam removal projects will encourage the state to increase restocking of alewives, bluebacks, and shad upriver in the mainstream. Diadromous species such as sea lamprey, rainbow smelt, American eel, white perch, and sea run trout benefit from dam removal on their own without restocking.

Appreciation of the benefits of dam removal has increased greatly in recent years. Dams that were used historically during the Industrial Revolution but are no longer functional, such as the Ipswich Mills Dam, are being increasingly removed, with results that are quickly appreciated by former opponents.

There’s good news about three low-head dams upriver from the Ipswich Mills Dam. The Willowdale Dam, which has an old notched weir-pool fish ladder, was scheduled to receive an Alaska Steeppass fish ladder through the State’s Division of Marine Fisheries in partnership with Foote Brothers and Greenbelt, but plans now are for a “nature-like fishway,” a new natural stream channel that will circumvent the dam. This will greatly improve access to Mass Audubon’s Ipswich River Sanctuary, where spawning herring have been observed at Bunker Meadows Pond. The Howlett Brook Dam received a new weir-pool fishway in the summer of 2023, which will open 8 miles of stream and 68 acres of historic pond spawning habitat for river herring.

The third mainstem dam is the Bostik-Finley Dam, 25 miles upstream in South Middleton, which presently has no passage and is currently the upper limit of anadromous fish range in the Ipswich River. The dam is expected to be removed in the summer of 2024. Success in all of these areas will hinge on the removal of the Ipswich Mills Dam. Fortunately, anadromous fish have frequently been observed spawning downstream when access to traditional upstream habitats is restricted.

There’s also good news about upstream watershed withdrawals from the Ipswich River. In March 2024, the Healy Administration awarded $2.3 million in grants to help seven communities with water sources in the Ipswich River Basin optimize their water supply and treat for PFAS chemicals as part of an effort by the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA) and the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) to maintain and improve access to clean and safe drinking water. Ipswich will use the funds to begin the development of a new water treatment plant, while Wilmington will use the grant money toward reducing or eliminating its draw of about 1.7 million gallons per day from the Ipswich River Watershed basin by connecting to the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA).

It was written by early explorers that there were so many large cod in the coastal Atlantic that you could “walk on their backs.” When coastal towns in New England allowed dams to be constructed even though it would kill the fisheries, fishermen complained loudly but were powerless against wealthy industrialists. We now understand that our river is an invaluable part of the Earth’s water cycle that makes all life possible, far more than a stream of water dumping its contents into the sea. For 14,000 years, the Ipswich River has shaped the land, nourished flora and fauna, and has been instrumental in the birth of our historic town. Since the 19th Century, its flow has been obstructed by the obsolete mill dam, which for over 100 years has served only as a reminder of man’s war with nature. We can write the next chapter of the history of the Ipswich River by freeing it from unnecessary man-made encumbrances and advocating for the fish and wildlife, as well as the human population that the river serves.

Sources and further reading:

- Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony Vol. I & Vol. II by Thomas Franklin Waters

- Ipswich Mills and Factories by Thomas Frank Waters

- The Industrial History of the Ipswich River by John Stump and Alan Pearsall for the 375th Anniversary of the Founding of Ipswich

- History of the Ipswich Mills Dam by John Stump for the Ipswich Museum

- Public Archeology Laboratory (PAL) Report for the Ipswich Mills Dam Removal Feasibility Study, June 2016

- Expanded Environmental Notification Form (2023)

- Ipswich Mills Dam feasibility study by the Ipswich River Watershed Association (IRWA)

- An Act to Prevent the Destruction of Alewives on the Ipswich River by Hailey McQuaid

- A Guide to Viewing River Herring in Coastal Massachusetts produced by the Massachusetts Corporate Wetlands Restoration Partnership

- A Report upon the Alewife Fisheries of Massachusetts by the Division of Fisheries and Game Department of Conservation published in 1920. Read on Archive.org

- Ipswich Targeted Watershed Project (Mass.Gov)

- Evaluation of Pre-Spawning Movements of Anadromous Alewives in the Ipswich River Using Radiotelemetry by Holly J. Frank, University of Massachusetts Amherst

- Traveling Through Time: Chebacco Lake Watershed’s History by Seaside Sustainability

- Ipswich Mill Dam Project by the Ipswich River Watershed Association

- Why We Love Beavers, Ipswich River Watershed Association

- Indigenous History of Essex County Massachusetts by Mary Ellen Lepionka

- Riverine System – an overview, ScienceDirect.com

- Successful Fish Passage Efforts Across the Nation, NOAA Fisheries

- Ipswich Mills Dam Removal Project, Ipswichmillsdam.comy

- A River Interrupted: Why Removing Defunct Dams is Critical for Restoring the Charles River, Charles River Watershed Association, January 20, 2022

- Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries 2022 Annual Report

- Ipswich annual herring count organized by IRWA

- A Survey of Anadromous Fish Passage in Coastal Massachusetts Boston Harbor, North Shore and Merrimack River, Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries, January 2005

- Evaluation of Pre-spawning Movements of Anadromous Alewives in the Ipswich River Using Radiotelemetry, a 2009 master’s degree thesis presented by Holly J. Frank, UMASS Amherst.

- Ipswich River Watershed 2000 Water Quality Assessment Report, Massachusetts Office of Environmental Affairs

- River Watch Water Quality Volunteer Monitoring Program 2015 Report, Ipswich River Watershed Association (IRWA)

- Ipswich River Watershed Action Plan, Horsley & Witten, Inc, 2003 for the MA Executive Office of Environmental Affairs

- Assessing Freshwater Habitat of Adult Anadromous Alewives Using Multiple Approaches, Maine and Coastal Fisheries, Vol. 4, 2012

- Saving the Egypt River (IRWA video)

- Ipswich Mills Dam Info Session December 14, 2022 (video)

- The River Agawam, an Essex County Waterway by George Francis Dow

- Evaluation of Pre-Spawning Movements of Anadromous Alewives in the Ipswich River Watershed (UMASS Scholarworks)

- Habitat assessment of Martins Pond by the Ipswich River Watershed Association (IRWA)

- Habitat assessment of Hood Pond in Topsfield by the Ipswich River Watershed Association (IRWA)

- Habitat assessment of Four Mile Pond in Boxford MA by the Ipswich River Watershed Association (IRWA)

- Howlett Brook Restoration Project (IRWA)

- Howlett Brook Fishway Construction Underway July 20, 2023 (IRWA)

- Integrated Watershed Management Modeling: Optimal Decision Making for Natural and Human Components: Victoria Zoltay, Paul Kirshen & Kirk S.Westphal

- Assessment of Habitat, Fish Communities, and Streamflow Requirements for Habitat Protection, Ipswich River, Massachusetts, 1998–99 by David S. Armstrong, Todd A. Richards, and Gene W. Parker

- The Merrimack River, National Park Service (NPS)

More about the Ipswich River

No “Bait and Switch” - Photo by David “Stoney” Stone Letter: The headline “Bait and Switch” in the November 25 article about the Ipswich Mills Dam was eye-catching but very misleading. Read this article at the Ipswich Local News.

No “Bait and Switch” - Photo by David “Stoney” Stone Letter: The headline “Bait and Switch” in the November 25 article about the Ipswich Mills Dam was eye-catching but very misleading. Read this article at the Ipswich Local News. Historic Survey of the Ipswich Mills Dam - Inventory No: IPS.9009: Ipswich Mills Hosiery Manufacturing Company Dam. Survey Form F (structure) submitted to the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Recorded by: Ted Dattilo for the Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc., May 2024. Received by the Mass. Historical Commission on Nov. 12, 2024 Historical Narrative: The history of the dam and how it relates to the development… Continue reading Historic Survey of the Ipswich Mills Dam

Historic Survey of the Ipswich Mills Dam - Inventory No: IPS.9009: Ipswich Mills Hosiery Manufacturing Company Dam. Survey Form F (structure) submitted to the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Recorded by: Ted Dattilo for the Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc., May 2024. Received by the Mass. Historical Commission on Nov. 12, 2024 Historical Narrative: The history of the dam and how it relates to the development… Continue reading Historic Survey of the Ipswich Mills Dam  Ipswich Receives $1.2M Grant For Dam Removal - Ipswich Mills Dam Removal Project Nationally Recognized Among 43 Projects to Receive U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Funding On April 23, 2024, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced that 29 states will receive just over $70 million to support 43 projects that will address outdated or obsolete dams, culverts, levees, and other barriers fragmenting… Continue reading Ipswich Receives $1.2M Grant For Dam Removal

Ipswich Receives $1.2M Grant For Dam Removal - Ipswich Mills Dam Removal Project Nationally Recognized Among 43 Projects to Receive U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Funding On April 23, 2024, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced that 29 states will receive just over $70 million to support 43 projects that will address outdated or obsolete dams, culverts, levees, and other barriers fragmenting… Continue reading Ipswich Receives $1.2M Grant For Dam Removal  Ipswich Mills Dam Feasibility Study - In 2010, the Ipswich Board of Selectmen voted to begin exploring removal of the Ipswich Mills Dam. The feasibility study was completed in March, 2019 and will set the stage for the Town's decision regarding the dam.… Continue reading Ipswich Mills Dam Feasibility Study

Ipswich Mills Dam Feasibility Study - In 2010, the Ipswich Board of Selectmen voted to begin exploring removal of the Ipswich Mills Dam. The feasibility study was completed in March, 2019 and will set the stage for the Town's decision regarding the dam.… Continue reading Ipswich Mills Dam Feasibility Study  The History of the Ipswich Mill Dam, and a Natural History of the Ipswich River - We measure history by time, but for the Ipswich River and its alewives, time could be running out. We can help preserve the human and natural history of the Ipswich River by freeing it from its man-made encumbrances.… Continue reading The History of the Ipswich Mill Dam, and a Natural History of the Ipswich River

The History of the Ipswich Mill Dam, and a Natural History of the Ipswich River - We measure history by time, but for the Ipswich River and its alewives, time could be running out. We can help preserve the human and natural history of the Ipswich River by freeing it from its man-made encumbrances.… Continue reading The History of the Ipswich Mill Dam, and a Natural History of the Ipswich River  Regarding the Removal of the Ipswich Mills Dam - By Ipswich resident Roger Wheeler On May 21, a yes vote to remove the head of tide Ipswich Mills Dam and free the river will provide Ipswich, Essex County, and New England with a rare fish-accessible river. This could be an extraordinarily uncommon river and watershed if all fish have accessibility at the head of… Continue reading Regarding the Removal of the Ipswich Mills Dam

Regarding the Removal of the Ipswich Mills Dam - By Ipswich resident Roger Wheeler On May 21, a yes vote to remove the head of tide Ipswich Mills Dam and free the river will provide Ipswich, Essex County, and New England with a rare fish-accessible river. This could be an extraordinarily uncommon river and watershed if all fish have accessibility at the head of… Continue reading Regarding the Removal of the Ipswich Mills Dam  The Miles River - Known in Colonial times as Mile Brook, the Miles River is a major tributary of the Ipswich River but has been diminished in volume by upstream use as a water supply. Evidence of the old Potter and Appleton mills can still be found near County Rd.… Continue reading The Miles River

The Miles River - Known in Colonial times as Mile Brook, the Miles River is a major tributary of the Ipswich River but has been diminished in volume by upstream use as a water supply. Evidence of the old Potter and Appleton mills can still be found near County Rd.… Continue reading The Miles River  The Choate Bridge - The American Society of Civil Engineers cites the Choate Bridge in Ipswich as the oldest documented two-span masonry arch bridge in the U.S., and the oldest extant bridge in Massachusetts. … Continue reading The Choate Bridge

The Choate Bridge - The American Society of Civil Engineers cites the Choate Bridge in Ipswich as the oldest documented two-span masonry arch bridge in the U.S., and the oldest extant bridge in Massachusetts. … Continue reading The Choate Bridge  When Herring Were Caught by Torchlight - In the late 19th Century, most of the men around the river would look forward to "herringing" when fall arrived. The foot of Summer Street was the best landing. One year so many herring were caught, they were dumped in the Parker River, and Herring did not return for many years.… Continue reading When Herring Were Caught by Torchlight

When Herring Were Caught by Torchlight - In the late 19th Century, most of the men around the river would look forward to "herringing" when fall arrived. The foot of Summer Street was the best landing. One year so many herring were caught, they were dumped in the Parker River, and Herring did not return for many years.… Continue reading When Herring Were Caught by Torchlight  Massachusetts Provincial Law: “An Act to Prevent the Destruction of Alewives on the Ipswich River” - Concerns about the environmental toll that dams have on the Ipswich River date to before 1773. … Continue reading Massachusetts Provincial Law: “An Act to Prevent the Destruction of Alewives on the Ipswich River”

Massachusetts Provincial Law: “An Act to Prevent the Destruction of Alewives on the Ipswich River” - Concerns about the environmental toll that dams have on the Ipswich River date to before 1773. … Continue reading Massachusetts Provincial Law: “An Act to Prevent the Destruction of Alewives on the Ipswich River”  Industrial History of the Ipswich River - The Industrial History of the Ipswich River was produced for the Ipswich 375th Anniversary by John Stump, , and Alan Pearsall.Historic photos are by Ipswich photographer George Dexter. … Continue reading Industrial History of the Ipswich River

Industrial History of the Ipswich River - The Industrial History of the Ipswich River was produced for the Ipswich 375th Anniversary by John Stump, , and Alan Pearsall.Historic photos are by Ipswich photographer George Dexter. … Continue reading Industrial History of the Ipswich River  The Town Wharf - The Ipswich Town Landing is one of several locations along the River where wharves were located over the centuries. … Continue reading The Town Wharf

The Town Wharf - The Ipswich Town Landing is one of several locations along the River where wharves were located over the centuries. … Continue reading The Town Wharf  Along the Ipswich River - Historic photos of the Ipswich River from original glass negatives taken by early Ipswich photographers Arthur Wesley Dow, George Dexter and Edward L. Darling. … Continue reading Along the Ipswich River

Along the Ipswich River - Historic photos of the Ipswich River from original glass negatives taken by early Ipswich photographers Arthur Wesley Dow, George Dexter and Edward L. Darling. … Continue reading Along the Ipswich River  A Photographic History of the Ipswich Mills Dam - Geologically, the Ipswich River is quite young. The Laurentide ice sheet during the most recent ice age receded to the northern border of Massachusetts around 14,000 years ago. As the ice sheet melted, the sea level rose about 100 ft. higher than current levels, putting much of the North Shore area temporarily under water until… Continue reading A Photographic History of the Ipswich Mills Dam

A Photographic History of the Ipswich Mills Dam - Geologically, the Ipswich River is quite young. The Laurentide ice sheet during the most recent ice age receded to the northern border of Massachusetts around 14,000 years ago. As the ice sheet melted, the sea level rose about 100 ft. higher than current levels, putting much of the North Shore area temporarily under water until… Continue reading A Photographic History of the Ipswich Mills Dam Ipswich River Watershed Association (IRWA)