The house at 26 East St. exhibits early 18th-century interior features, but structural evidence, including a large walk-in fireplace, heavily chamfered exposed beams, and an asymmetrical facade suggest that half of the house may have been constructed in 1687 for Deacon John Staniford (1648-1730) and his wife Margaret. In the Nineteenth Century, the house was owned by a woman named Polly Dole, which is how it acquired its name. In the 1960s the house was purchased by John Updike, and it was here that he wrote some of his most popular works.

This saltbox house has elements from 1687 but acquired its current form in 1720. On the right front is a large front living room with a low ceiling, wide board floors, and a walk-in fireplace. The hewn summer beam in the middle of this room is suspended by a cable to an unusual triangular frame in the attic made of beams. The left side of the house is smaller than the right side, which appears to be the original “half house.”

The downstairs left side has a massive fireplace, while the other three front rooms have smaller fireplaces typical of the 1700s. The stone foundation and the fireplaces were constructed at the same time, around 1720, as indicated by the clay and sand mortar, and the reuse of old odd-sized, handmade bricks. Near each corner of the framing for the original roof of the one-over-one right side of the house are unusual, angled mortises for braces that no longer exist.

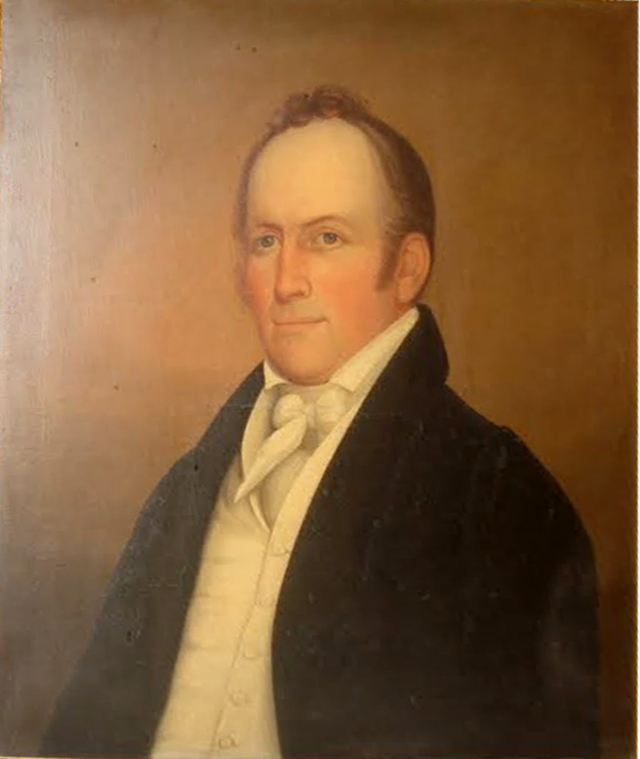

The right side of this house is believed to have been constructed in 1687 for Deacon John Staniford (1648-1730) and his wife Margaret, the daughter of Thomas and Martha (Lake) Harris. John Staniford bore the title of Deacon in his old age. He was said to have been a man of intellectual qualities and “much occupied with duties which require legal knowledge.” Capt. Jeremiah Staniford inherited the homestead of his father.

In 1806, Daniel Staniford of Boston received the homestead, including a house and barn and the land under them, as a judgment against William Staniford for $1393.97 (179:114). He and his wife Lucy sold it to Nathaniel Lord 3rd on March 5, 1811, for $810.00 (193:115).

Nathaniel Lord sold to two “well-remembered” women, Lucy Fuller and Polly Dole, “the homestead of the Capt. Jeremiah Staniford, deceased” on April 29, 1837 (301: 268). The deed describes a line through the middle of the front door and the chimney, one side of the house and land for Lucy Fuller, and the other side for Polly Dole. The 1856 Ipswich map shows the house owned by Fuller and Dole.

At the Old North Burying Ground is the gravestone of Lucy Fuller, who died in 1864. She was the widow of James Fuller, who died Oct. 21, 1794.

The administrator of Lucy Fuller’s estate sold half a dwelling house to Daniel S. Burnham on Aug. 23, 1865 (692: 195). The 1872 map shows the house owned by “D. Burnham.” In the next deed, he sold the half house “bounded by Polly Dole” to Charlotte Burnham, and in the next deed, she sold it to James H. Fagin.

Why the house has long been named after Polly Dole is uncertain. She is probably Polly Swett, who married Jacob Dole on Nov. 2, 1814, in Rowley. He was lost at sea in 1821. She would not be Polly Dole, the daughter of Capt. David Dole of Newbury. She was born on Nov. 18, 1784, and died June 18, 1858 (aged 73) and never married. Several deeds show her residence in Newbury.

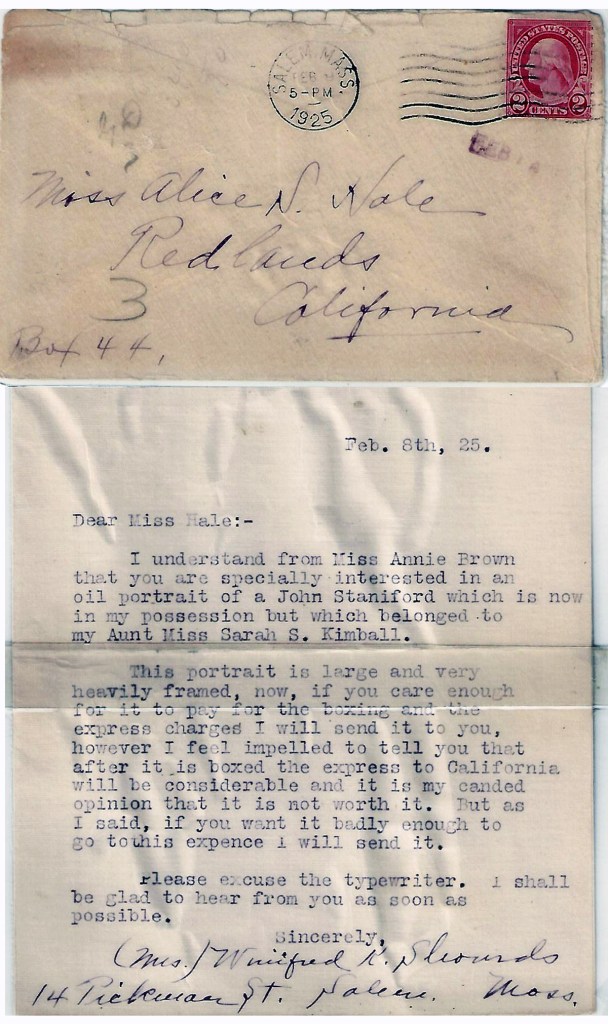

A memorial in Section A of the Old North Burying Ground is dedicated to John Staniford, Joseph Farley and their Kimball relations, including Sarah Kimball, mentioned in the letter below:

From the MACRIS site: John Staniford bought this lot from John Baker in 1687 (33:31), but stylistic evidence suggests a construction date of about 1720. There are, however, 17th-century elements incorporated into the house, including roof purlins and a heavily chamfered fireplace lintel with a fine lamb’s tongue stop, which are probably reused materials from an earlier structure. The majority of the trim throughout the house is of 18th and 19th-century vintage. A staircase brought from a house on Cape Cod was installed in the western half of the house.

Polly Dole House, 26 East St. Preservation Agreement

The house at 26 East St. in Ipswich has a Preservation Agreement held by the Ipswich Historical Commission.

- East-26-polly-dole-preservation-agreement-page-1

- East-26-polly-dole-preservation-agreement-page-2

- East-26-polly-dole-preservation-agreement-page-3

- East-26-polly-dole-preservation-agreement-page-4

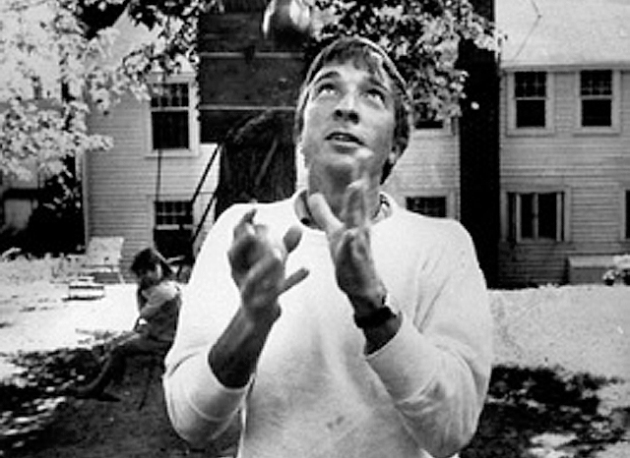

John Updike wrote the following article in Architectural Digest about living in the Polly Dole House in Ipswich:

“Most Americans haven’t had my happy experience of living for thirteen years in a seventeenth-century house since most of America lacks seventeenth-century houses. But not New England, and especially not Ipswich, Massachusetts, which, thanks to an early boom and a long stagnation, has more so-called seventeenth-century houses still standing than any other town in the nation. “So-called” because old wooden houses aren’t simple to date.

“The early Yankees, thrifty and handy, reused and transposed major worked timbers without any consideration for the antiquarians of the future. A noble chamfered summer beam, for instance, may certainly date from before 1680, but be worked in with structured members from several decades later, in a room with raised-field panelling from 1750, in a house fitted with new windows and staircases in the nineteenth century, and most recently, clapboarded in 1950. The old frameworks were sometimes completely swallowed in later renovations, and the original shape of the place was detectable only in the attic and around the cellar stairs. The foundation itself may have belonged to an earlier, quite vanished house. Architectural historians use the term first-period, signifying a date before 1720.

“The house I, my wife, and four children lived in was called, on a plaque beside the front door, the Polly Dole House and given a date of 1687, though one expert sneeringly opined that dating it prior to 1725 would compromise his integrity. A seventeenth-century house can be recognised by its steep roof, massive central chimney, and utter porchlessness. Some of those houses have a second-story overhang, emphasising their medieval look. The gables are on the sides. The windows were originally small, with fixed casements and leaded diamond panes. The basic plan called for two rooms over two, the fireplace opening into each room; a later plan added half-rooms behind, creating the traditional saltbox shape. Inside the front door—at least our front door—a shallow front hall gave onto an exiguous staircase squeezed into the space left by the great brick core at the heart of the house.

“The fireplace, with its cast-iron spits and bake ovens, had been the kitchen. The virgin forests of the New World had contributed massive timbers, adzed into shape and mortise-and-tenoned together, and floorboards up to a foot wide. The Polly Dole House had a living room so large that people supposed the house had originally been an inn, on the winding old road to Newburyport, which ran close by. Polly Dole was a shadowy lady who may have waited on tables; we never found out much about her, though local eyebrows still lifted at her name. The big room, with its gorgeous floorboards, was one you sailed through, and the furniture never stayed in any one place.

The walk-in fireplace, when the three-foot logs in it got going, singed your eyebrows and dried out the joints of any chair drawn up too cosily close. In the middle of the summer beam, a huge nut and washer terminated a long steel rod that went up to a triangular arrangement of timbers in the attic; at one point, the house had been lifted by its own bootstraps. I used to tell my children that if we turned the nut, the whole house would fall down. We never tried it.

“The decade was the sixties, my wife and I were youngish, and the house suited us just fine. It was Puritan; it was back-to-nature; it was less is more. A seventeenth-century house tends to be short on frills like hallways and closets; you must improvise. A previous owner had put a pipe and a pole in a small upstairs room to make a walk-in closet; fair weather or foul, I would hike from our bedroom to my clothes every morning. I find I have no memory at all of where my wife kept hers. Perhaps, it being the sixties, she only needed a miniskirt and a lumberjack shirt.

“Our children, four of them, slept in four little rooms in a row above the long kitchen, which for a time had been two kitchens, a partition intervening. There had been only two children when we moved in, and if there had been six little rooms, we might have felt obliged to fill them up. When they were awake and downstairs, the children reached around and around the central brick mass with its four fireplaces on a counterclockwise route that went front hall, living room, kitchen, dining room, and front hall.

“The living room, with its low smoky-beamed ceiling, cheerfully accepted our butterfly chairs and Danish modern and glass-and-chrome coffee table. Such austere furniture looked in tune, on the broad old boards, under the slightly swaybacked beams. The ancient house felt oddly up-to-date in its serene lake of Victorian complications. Around 1940, an Ipswich eccentric (one of many), a bachelor who, besides fixing up old houses, went, in his quest for religious authenticity, from the Anglican priesthood into that of Russian Orthodoxy, had rescued the place from tenement status. At the Depression nadir of its fortunes, we were told that not only too many people had inhabited the rooms but a flock of chickens as well. The architect-priest had in his renovations installed generous twelve-over-twelve sash-hung windows, and this fenestration dispelled any lingering gloom.

“One felt Puritan claustrophobia only in the cellar, among the fieldstone foundation walls, piled up without much benefit of mortar, and threaded with a worrisome inheritance of deteriorating pipes and wires. There was no sewer connection, only a cesspool in the backyard, which, by the inexorable laws of hydraulics, would sometimes overflow into our kitchen sink. In the attic, there were many loose boards, some pink fluff pretending to be insulation, a fine view over the rooftops toward the town wharf, a ramshackle TV aerial, and, in the end, tons of stacked New Yorkers.

“How did inhabiting such an antique affect our lives? We joined the local historical society, for one thing. We worked up, for the benefit of our fellow first-period owners, a smattering of small talk about gunstock posts, clamshell plaster, purlin-type roof construction, and original brick noggin. First-period houses, mixed in with creditable specimens of the Georgian and Federal styles, were strung up and down our street, called High at one end and East at the other.

“Architectural conservation was freshly in the air; Ipswich’s old houses, left for centuries to fend for themselves, were no longer being torn down and, rather, were being fixed up by newcomers—commuters and artisans with beards, pigtails and a regard for history. We ourselves felt part, deeply and effortlessly, of the community because we owned a piece of its past, sleeping and eating in rooms where fourteen or so generations had left their scuff marks.

“The straightforward, hearth-centered architecture of our house must have strengthened our family sense. Once we moved, the fact is, things fell apart. The big nut and bolt were holding us together as well. Erwin Panofky, in his elegant monograph Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism, describes the architectural spirit of medieval cathedrals as one of manifestation—the principle of elucidation and continuous clarification that informs scholastic philosophy.

“Each rib of the ceiling vault, for example, can be followed down into the compound columns that line the nave. Abbot Suger, the first known architectural theorist of the Middle Ages, wrote the “principle of transparency.” “And so,” Panofsky tells us, “did High Gothic architecture delimit interior volume from exterior space yet insist that it project itself, as it were, through the encompassing structure; so that, for example, the cross-section of the nave can be read off from the façade.”

“So, too, the layout of the rooms—two above, two below—can be read off the façades of the houses the Puritans built, and a certain transparency quickens the life within. The beams are plain to see in the rooms; organic grains and irregularities animate the floors and walls; there are no hidden passageways, no cunning closets, no dumbwaiters, no cubbyholes for servants. To wake and work in such a house felt like an honor, a privileged access to the elemental clarity of the spirit that created the first Puritan settlements in the New World.”

Sources:

- Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony by Thomas Franklin Waters

- Architectural Digest

- MACRIS

Where is the John Staniford portrait? Thank you Mac

Hello? Where is the John Staniford portrait located?

Okay if Polly Dole is Polly Swett Dole.

There’s another Polly Dole whose father David Dole’s will was probated in mid-1837, leaving Polly as sole heir, sharing the estate with her brother, in Newbury. 10 miles from Ipswich. Apparently, she never married and her mother’s family (Judith Pearson) was prospering nearby, including bakeries and mills. She’s famous for her cooking including “Polly Dole Cake” which has brandy in it. She died in June 1858. The family trees imply their Dole lines don’t intersect much at all; both Polly Dole ancestries include the Pearsons of Rowley. So anyway . . . how do we know for sure which Polly Dole it was? I understand that know more, to say Polly Swett Dole who bought the inn with Lucy Fuller. I already believe you.

I am very proud of my Staniford heritage.

I so love finding these bits of history online.

Thank you so much.

Bonnie Bohman – descendent of Barbara Louise, daughter of Arthur Fowler Staniford.

This John Updike commentary is priceless. Wonderful come across it especially since I pass this house every day.