Capt. Jonathan Burnham with the Hampton Company arrived in Ipswich on the morning of April 21, 1775, after an all-night march, and found the town panic-struck. The town was nearly defenseless, as more than three hundred Ipswich men had marched off with their Ipswich captains to fight the British regulars at Concord and Lexington. A rumor had spread that two British ships which had anchored in the river were full of British soldiers on their way to burn the town. About two hundred men, many elderly, were mustered to protect the town, and Capt. Burnham stayed as their commander.

Thomas Franklin Waters wrote about the sequence of events in his book, “Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony“:

“It has come down in history as the ‘Great Ipswich Fright,‘ and it furnished Mr. Whittier material for a very spirited tale in his Prose Miscellanies.” The innocent occasion of it all was the discovery of some small vessels near the entrance of Ipswich River, one at least known to be a cutter, and it was believed that they had come to relieve the captives there in the Ipswich jail. We may be sure there was fright with good reason at the farms on Castle Hill and Castle Neck when those British vessels were seen standing in over the bar.”

Capt. Jonathan Bumham at the head of his Hampton Company arrived in Ipswich the morning after an all-night march. According to his own story, he found the town panic-stricken because, “two Men of Wars tenders were in the river full of men and would land and take twenty British soldiers out of the jail that were taken prisoners at Lexington battle and would burn the town, so we stayed that day and night.”

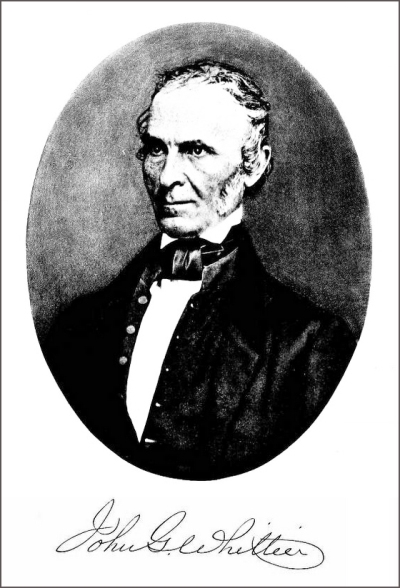

The following story is from John Greenleaf Whittier’s “The Great Ipswich Fright.”

The Frere into the dark gazed forth

The sounds went onward towards the north

The murmur of tongues the tramp and tread

Of a mighty army to battle led

The 21st of April, 1775 witnessed an awful commotion in the little village of Ipswich. Old men, and boys, (the middle-aged had marched to Lexington some days before) and all the women in the place who were not bedridden or sick, came rushing as with one accord to the green in front of the meeting house.

A rumor, which no one attempted to trace or authenticate, spread from lip to lip that the British regulars had landed on the coast and were marching upon the town. A scene of indescribable terror and confusion followed. Defense was out of the question, as the young and able-bodied men of the entire region had marched to Cambridge and Lexington.

The news of the battle at the latter place, exaggerated in all its details, had been just received; terrible stories of the atrocities committed by the dreaded “regulars” had been related; and it was believed that nothing short of a general extermination of the patriots–men, women, and children–was contemplated by the British commander. Almost simultaneously the people of Beverly, a village a few miles distant, were smitten with the same terror. How the rumor was communicated no one could tell. It was there believed that the enemy had fallen upon Ipswich and massacred the inhabitants without regard to age or sex.

It was about the middle of the afternoon of this day that the people of Newbury, ten miles farther north, assembled in an informal meeting, at the town-house to hear accounts from the Lexington fight, and to consider what action was necessary in consequence of that event. Parson Cary was about to open the meeting with prayer when hurried hoof beats sounded up the street, and Ebenezer Todd of Rowley, loose-haired and panting for breath, rushed up the staircase. “Turn out, turn out, for God’s sake,” he cried, “or you will be all killed! The regulars are marching on us; they are at Ipswich now, cutting and slashing all before them!”

Universal consternation was the immediate result of this fearful announcement; Parson Cary’s prayer died on his lips; the congregation dispersed over the town, carrying to every house the tidings that the regulars had come. Men on horseback went galloping up and down the streets, shouting the alarm. Women and children echoed it from every corner. The panic became irresistible, uncontrollable. Cries were heard that the dreaded invaders had reached Old Town Bridge, a little distance from the village, and that they were killing all whom they encountered. It was resolved to take flight. All the horses and vehicles in the town were put in requisition; men, women, and children hurried as for life towards the north. Some threw their silver and pewterware and other valuables into wells.

The news spread spontaneously as far as New Hampshire, and in every place, the report was that the regulars were but a few miles behind them, cutting and slashing everyone in sight. Propositions were made by some persons to destroy the Thurlow’s Bridge and the one over the Parker River, but it was heard that they had advanced as far as Artichoke River, and at Newburyport, they were at Old Town Bridge. Hundreds on foot and on horses sped north to escape the regulars.

Large numbers crossed the Merrimac and spent the night in the deserted houses of Salisbury, whose inhabitants, stricken by the strange terror, had fled into New Hampshire, to take up their lodgings in dwellings also abandoned by their owners. A few individuals refused to fly with the multitude; some, unable to move because of sickness, were left behind by their relatives.

One old gentleman, whose excessive corpulence rendered retreat on his part impossible, made a virtue of necessity; and, seating himself in his doorway with his loaded king’s arm, upbraided his more nimble neighbors, advising them to do as he did, and “stop and shoot the devils.”

Many ludicrous instances of the intensity of the terror might be related. One man got his family into a boat to go to Ram Island for safety. He imagined he was pursued by the enemy through the dusk of the evening, and was annoyed by the crying of an infant in the afterpart of the boat. “Do throw that squalling brat overboard,” he called to his wife, “or we shall be all discovered and killed!” A poor woman ran four or five miles up the river, and stopped to take breath and nurse her child when she found to her great horror that she had brought off the cat instead of the baby!

All through that memorable night the terror swept onward toward the north with a speed that seems almost miraculous, producing, everywhere, the same results. At midnight a horseman, clad only in shirt and breeches, dashed by our grandfather’s door, in Haverhill, twenty miles up the river. “Turn out! Get a musket! Turn out!” he shouted; “the regulars are landing on Plum Island!” “I’m glad of it,” responded the old gentleman from his chamber window; “I wish they were all there, and obliged to stay there.” When it is understood that Plum Island is little more than a naked sand ridge, the benevolence of this wish can be readily appreciated.

All the boats on the river were constantly employed for several hours in conveying across the terrified fugitives. Through “the dead waste and middle of the night” they fled over the border into New Hampshire. Some feared to take the frequented roads and wandered over wooded hills and through swamps where the snows of the late winter had scarcely melted. They heard the tramp and outcry of those behind them and fancied that the sounds were made by pursuing enemies. Fast as they fled, the terror, by some unaccountable means, outstripped them. They found houses deserted and streets strewn with household stuff, abandoned in the hurry of escape.

Towards morning, however, the tide partially turned. Grown men began to feel ashamed of their fears. The old Anglo-Saxon hardihood paused and looked at the terror in its face. Single or in small parties, armed with such weapons as they found at hand, among which long poles, sharpened and charred at the end, were conspicuous, they began to retrace their steps. In the meantime, the good people of Ipswich who were unable or unwilling to leave their homes became convinced that the terrible rumor that had nearly depopulated their settlement was unfounded.

Among those who had there awaited the onslaught of the regulars was a young man from Exeter, New Hampshire. Becoming satisfied that the whole matter was a delusion, he mounted his horse and followed after the retreating multitude, undeceiving all whom he overtook. Late at night he reached Newburyport, greatly to the relief of its sleepless inhabitants, and hurried across the river, proclaiming as he rode the welcome tidings. The sun rose upon haggard and jaded fugitives, worn with excitement and fatigue, slowly returning homeward, their satisfaction at the absence of danger somewhat moderated by an unpleasant consciousness of the ludicrous scenes of their premature night flitting.

Flight from Rooty Plain

Mrs. Alice P. Tenney in 1933 provided an amusing story of the fear that struck Rooty Plain, also called “Millwood,” a thriving little mill community along today’s Rt. 133 in Rowley was part of Linebrook Parish.

“News arrived in Rooty Plain that the Regulars had come into Ipswich, and every man in Rooty Plain was called for to meet the enemy. Mr. Phillips was out in his field with his team; he left the team for the boys to take care of, and went into the house and asked for a pair of clean stockings. Said his wife to him, “Why what is the matter!” “Matter enough,” he replied. “The regulars have come into Ipswich!” And forthwith he and all men in the aforesaid Rooty Plains started out to meet the foe.

“One old lady, Mrs. Wood started from Woods Hill and traveled to Col. Adams beyond Georgetown corner carrying with her a gun that had no lock; probably to defend herself in case of an attack from the invading foe. The women in Rooty Plain being deprived of the protection of their liege lords, resolved to get together in some out-of-the-way place and spend the night. So a Mrs. Woodbury took old Mrs. Hopkins, aged more than ninety years and not being able to walk, and placed her on some kind of a vehicle and hauled her up as far as Straight Rock. She left her while she went to see Mrs. Phillips to invite her to join her party in going to Mrs. Lancaster’s house, which they considered about as far out-of-the-way as was possible for them to get.

“Mrs. Phillips thought at first she could not leave her house, but the children pleaded so hard with her to go, she at length consented to go if they would eat their supper first. So they ate a little, and then with Mrs. Woodbury, they went back where she left the old lady. After Mrs. Phillips started she stopped and looked back to see her house, thinking before morning it might be laid in ashes.

“They started on their way with old Lady Hopkins, far out of the way. When they reached Great Rock Brook, they met Mrs. Lancaster’s family with their ox team, carrying beds, bedding, and food, for they were trying to flee from the enemy, so they were going into the woods to spend the night; but when they met their neighbors, that were going to their house, thinking that the safest place. So Mrs. Lancaster’s family turned their team and went home with them. After reaching their destination, they hung quilts up to the windows to exclude all light. Children were put to bed, while the old folks sat up and waited for the enemy to come.

“Daylight came at length, but no enemy; and they began to be impatient. Mrs. Woodbury began to think she would like to see what had become of her house; so she and two young ladies started out across the pasture to see what was to be seen. They came in sight of the house, and it was just as it was left on the preceding night. They passed on a little farther and saw one lone man coming, riding very fast. They began to ask each other, if it was best to speak him, or let him pass, but finally came to the conclusion it was only one man, and they would speak. It was Mr. Woodbury, who had come to tell them that the regulars had not come into Ipswich.

Apparently, the alarm was caused by a few innocent sheep that were pastured on the Great Neck. (*During the siege of Boston, which began immediately after the battles at Concord and Lexington, the British navy frequently raided coastal grazing areas to supply it with fresh provisions of meat from cattle and sheep.)

Thus fled all the inhabitants of Rooty Plain except for one aged man, Mr. Stephen Dresser who thought he would sit down a while and smoke his pipe, and wait for the enemy. So he smoked and waited, but they didn’t come. He smoked again and waited, but they didn’t come. Smoked again and went to bed, and had quite a comfortable night’s sleep.”

Download this story as a PDF file

Further reading:

- Sam Sherman, Ipswich, Stories from the River’s Mouth.

- John Greenleaf Whittier, The Great Ipswich Fright

- Thomas Franklin Waters, Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony

Those poor people must have been scared out of their wits … BUT the lady that brought her cat instead of her baby, that’s unbelievable!